What is leprosy?

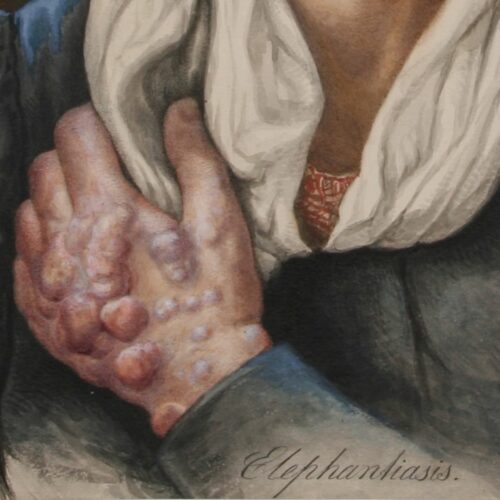

Leprosy is a chronic infectious disease caused by the leprosy bacteria, Mycobacterium leprae. The disease mainly affects the skin, the mucous membranes in the upper respiratory tract, the eyes and the peripheral nerves. The symptoms can manifest themselves in many different degrees and variants, and a distinction has traditionally been drawn between two main types of leprosy: the lepromatous and the tuberculoid forms. Today, leprosy can be cured by a combination of different types of antibiotics.

Despite the fact the disease is infectious, the risk of infection and developing leprosy is small.

For more information about the disease, its treatment, and its current global prevalence, we recommend visiting the World Health Organization’s website.

Symptoms and different forms

The symptoms can manifest themselves in many different degrees and variants, and a distinction has traditionally been drawn between two main types of leprosy: the lepromatous and the tuberculoid forms. Without treatment, the disease will gradually worsen and may result in permanent injury and disability.

Modes of infection

Transmission mainly occurs through droplet infection, but the risk of transmission is low and usually requires close and prolonged contact with the infected person. Even then, only a small proportion of those infected become ill. For the disease to develop, several conditions must be present in addition to the bacterium, and nutrition and genetics are decisive additional factors.

A disease with many names

Leprosy or Hansen’s disease? The disease and the people affected by it have been known by different names throughout the ages, both in the medical community and among the general population. It is important to be aware of the terms we use, as older terms may be considered offensive today.

One disease, many myths

Leprosy is one of the oldest known diseases and has often been associated with religious and social stigmas. People all over the world have experienced the disease having major social consequences, but far from all were ostracized or isolated. Many of those who experienced leprosy received support and help from their families, communities and others.

The spread of the disease in Norway

Leprosy appears to have been present in Norway since the 10th century. In medieval times, the disease was prevalent throughout Europe but it declined during the course of the 16th century. In most European countries, it has not been a major problem since that time. In Norway on the other hand, there were a number of cases in the 17th and 18th centuries, and there appears to have been a resurgence in the 19th centuries, particularly along the west coast.

For a long time, there was uncertainty about how widespread the disease actually was. Leprosy could often be mistaken for other diseases, and with a widely scattered population, many people had very little contact with the authorities. The government feared that the disease was spreading more and more rapidly, and this led to a nationwide count that was carried out by clergymen in 1836, 1848, and 1852. These showed an increase in prevalence from 5 to 11 cases per 10,000 inhabitants.

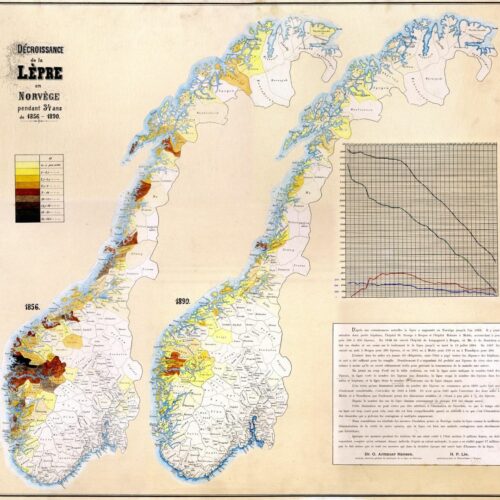

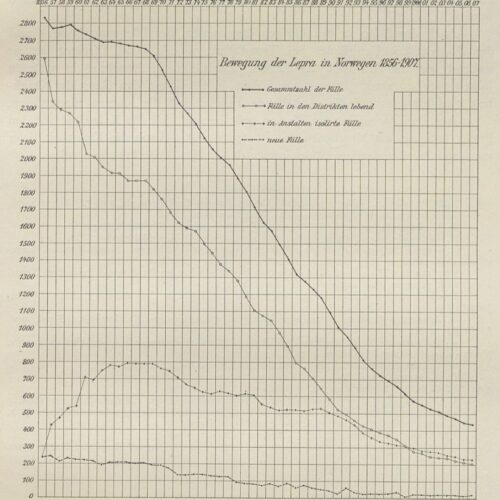

Although the accuracy of the census was uncertain, it was enough to cause concern. Leprosy was seen as one of the biggest threats to public health, and there was a significant need for more knowledge about the disease and measures to limit its spread. In 1854, a new governmental position was established: ‘Chief Medical Officer for Leprosy’. One of the medical officer’s first tasks was to establish a more accurate system for registering those affected by leprosy. From 1856, the new leprosy registry gradually painted a more reliable picture of the disease’s prevalence.

It became apparent that there were significant geographical variations. The disease was most common in the coastal areas between Stavanger and Trondheim, although there were also a number of cases further north along the coast. There was not much prevalence inland or in the eastern parts of Norway. The majority of those afflicted were poor fishermen and farmers from Hordaland and Sogn og Fjordane. In some areas, as many as three per cent of the population was affected.

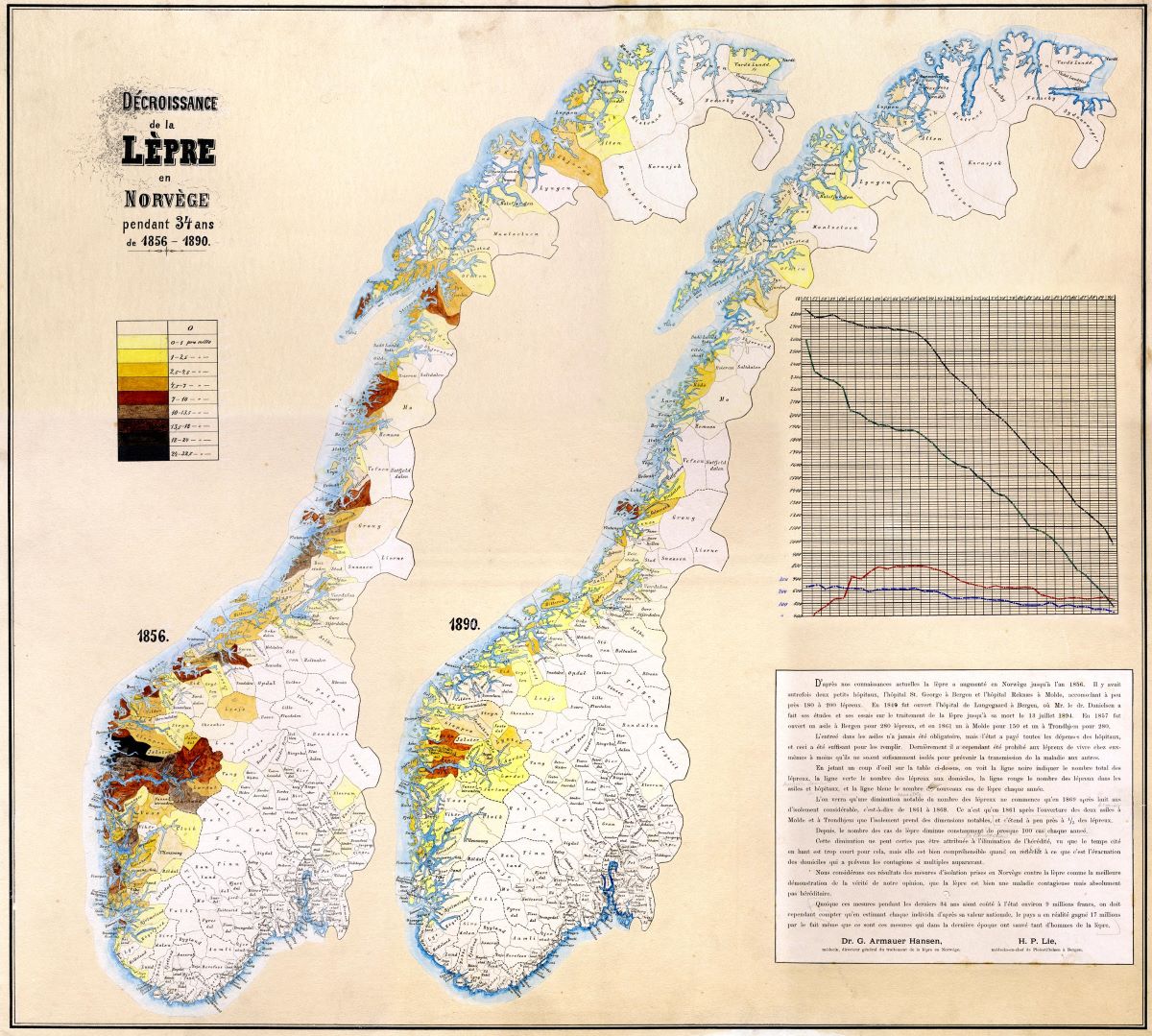

After 1856, the spread of the disease decreased relatively quickly. The difference between the colour-coded maps from 1856 and 1890 are striking. We now know that a number of different factors affect who is susceptible and how many people contract the disease, such was lifestyle, diet and genetic predisposition. The improvement in the standard of living in the second half of the 19th century contributed to the decline of new cases.

In the 1850s, Sunnfjord in Sogn was a hotspot for leprosy. There were particularly many cases in Naustdal, Kinn, and Askvoll. By around 1900, this changed. The physician H. P. Lie described as a ‘staggering situation’, the fact that Pleiestiftelsen in Bergen was admitting increasing numbers of patients from Fjell outside Bergen. Between 1896–1898, one in six new admissions were from Fjell, but from 1899–1901, this had increased to one in four – 10 of the 39 residents were from Fjell.

In the second half of the 19th century, the number of new cases gradually decreased. In the five-year period between 1861–1865, 1,040 new cases were registered. Between 1866 and 1,870 this number had decreased to 987, and in the five-year period between 1871-1875 it had decreased again to 720. In the following five-year periods, the numbers were 506, 373, 261, 162, and 89. By the start of the 20th century, there were 113 new cases between 1901–1905, and in the subsequent five-year periods there were 73, 51, 24 and 15 new cases. Between 1926–1929, there were three new cases. The last people diagnosed with leprosy who were thought to have contracted the disease in Norway were diagnosed in 1951.

Theories about the cause of the disease

From Middle Ages up until the modern era, there have been many different views about the nature of the disease and its causes. Most people saw leprosy as a divine punishment, a disease that affected sinners who only had themselves to blame.

Among medical professionals, opinions were divided. There long reigned uncertainty about whether leprosy was a specific disease or a more general condition that affected the malnourished and unclean people of the countryside. The miasma theory and heredity were long cited as common explanations for the cause of the disease. Contagion was also understood in different ways, and it wasn’t until the 1860s that bacteria became the dominant explanation for the spread of the disease.

Heredity?

Danielssen observed that a large proportion of the residents at St. Jørgen’s Hospital had family members or other relatives with the same disease, although he did not observe hospital staff or others in contact with patients being infected. Danielssen therefore concluded that leprosy was a hereditary blood disease.

Contagion?

One of the first to advocate that leprosy was infectious was Ove Guldberg Høegh, the father of the National Leprosy Registry of Norway. The registry enabled Armauer Hansen to demonstrate that isolation through hospitalisation reduced the number of new leprosy cases, indicating that the disease was infectious.

Early medical activity and research

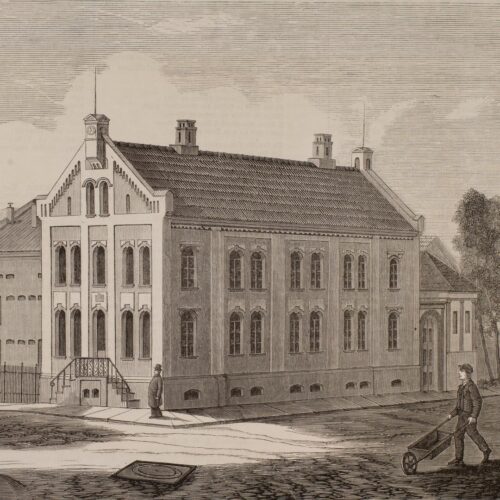

Although St. Jørgen’s Hospital was established as early as the 15th century, not much medical activity occurred there until the turn of the 18th and 19th centuries. At that time, a few of the city physicians monitored the residents to some extent, and some of them also attempted curative trials. Both J. A. W. Büchner and Christian Wisbech tested treatments in the last decades of that period, but without any significant results.

These were, however, only sporadic experiments, and the hospital did not have its own physician. The credit for the hospital finally acquiring its own physician in 1817 must be given to a clergyman. In 1816, the hospital chaplain Johan Ernst Welhaven published a report in which he describes the symptoms of many of the residents of St. Jørgen’s, proposed theories about possible causes of the disease, and criticised the conditions at the hospital. In response, the state decided the following year that the hospital should have its own physician. Additionally, the number of staff was to increase, and patients were to receive free medication.

This was an significant change, at least on paper. Army physician Jacob C. Teuscher was employed as the hospital’s ‘surgeon’ in 1817. It seems, however, that his activity did not result in much change for the residents. The superintendent suggested the medical post be abolished, as it had not resulted in a reduction in mortality. Brigade medical officer Hjort, who travelled around the western part of Norway in 1832, was also critical, suggesting that the physician should only ‘attend to patients when other illnesses arose’ and was not to attempt to cure them of leprosy. Any attempts would in any case ‘have been futile under the institution’s highly deficient structure’. In his opinion, the fact that they lacked bathing facilities was an especially severe hinderance.

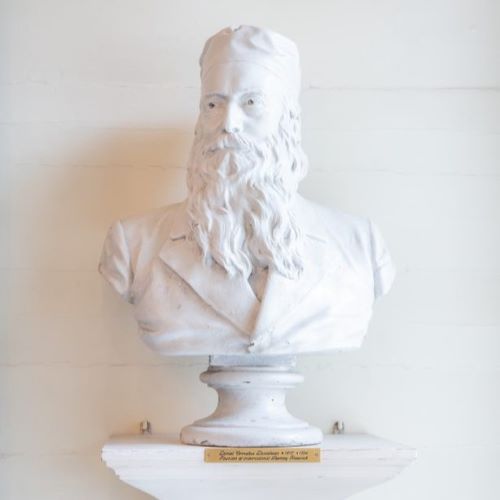

It was not until Daniel C. Danielssen began his work at St. Jørgen’s Hospital in 1839 that the monitoring of residents became more regular, as did systematic examinations and treatment trials. Still, opportunities were limited, not only because of the old and inadequate buildings, but also because the residents were reluctant to try the proposed treatment methods. With Danielssen, the hospital had, for the first time, a physician who devoted almost all his time to leprosy and who acquired significant expertise about the disease. After the opening of Lungegård Hospital in 1849, most of the scientific experiments and curative trials were conducted there.

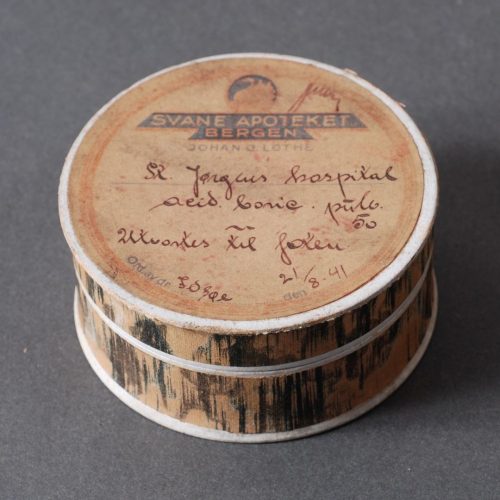

During the 19th century, numerous physicians devoted parts or all of their careers to leprosy. Some of them were associated with multiple leprosy hospitals, either concurrently or at different times, and others also worked with other hospitals in Bergen or elsewhere in Norway. The physicians had differing opinions about many things, including the cause of the disease and the best way to treat it. What they all had in common was perseverance and the extensive efforts they made to gain more knowledge about the disease – through autopsies, observations, analysis of blood and urine, and later, microscopy of tissue samples. Some of them believed it was possible to stop the progression of the disease, or possibly even cure it in its earlier phases, by adhering to strict diets, maintaining good hygiene, frequent bathing, and by regularly exercising in fresh air. Others believed that medication was the answer, and trialled a range of remedies such as mercury, arsenic, guano, chaulmoogra oil, creosote, carbolic acid, and various agents containing phosphorus and iodine.

The great interest and effort invested aimed to position Bergen at the forefront of research on this specific disease, both in terms of understanding what caused it and potential measures to prevent its spread.

Quicksilver and charlatans

A number of the city physicians attempted to cure some of the residents at St. Jørgen’s Hospital as early as the first decades of the 18th century. They initially placed most emphasis on diet, but bathing and mercury treatment were later trialled. A number of well-known charlatans – with no medical education – also offered various treatments.

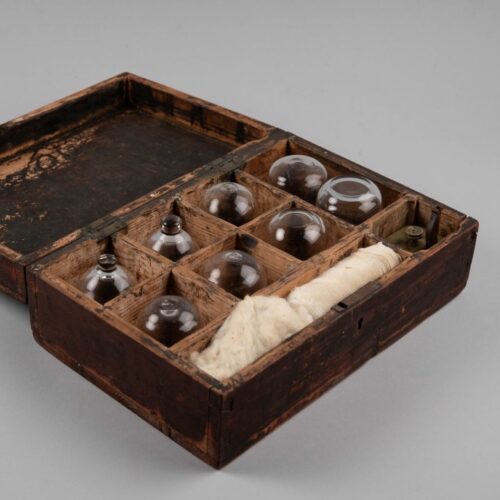

Cupping and bloodletting

Bloodletting was a common treatment method in times past. It involved draining varying amounts of blood from the patient. The procedure could be performed using leeches, by making incisions in the skin that would be left to bleed, or by cupping. Cupping involved small incisions being made in the skin before a hollow object was placed over the wounds to draw blood.

‘Reluctance’ to curative trials

The annual reports of the doctors associated with St. Jørgen’s Hospital describe the residents not following the doctors’ suggestions for possible treatments, nor advice about diet and hygiene. They describe in particular how patients had little inclination to take medicine over a prolonged period, despite the doctors’ attempts to persuade them.

Resistance to autopsies

If many of the residents at St. Jørgen’s Hospital were sceptical about trying new treatments, they had even more reservations about autopsies – which at that time were also referred to as ‘corpse examinations’ or ‘sections’. When Danielssen wanted to start carrying out autopsies in the 1840s, he was met with shock, fear, and outrage.

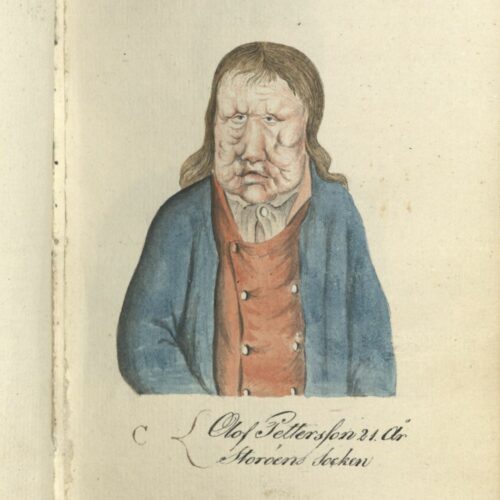

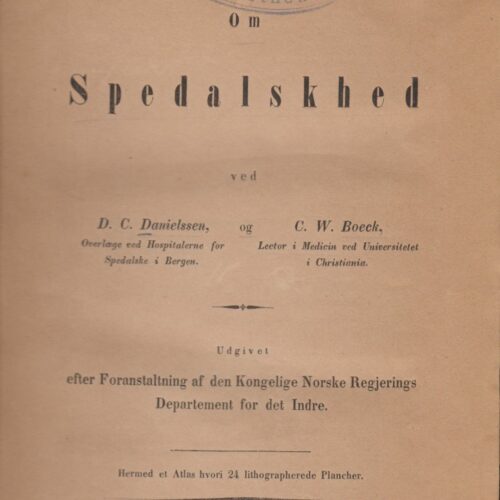

The book ‘On Leprosy’ from 1847

The written work was the first modern scientific description of leprosy and formed the basis for leprosy research for a long time to come. Leprosy was defined for the first time as a specific disease and clearly distinguished from other skin conditions. The book was published in both Norwegian and French, earning international recognition for its authors, Danielssen and Boeck.

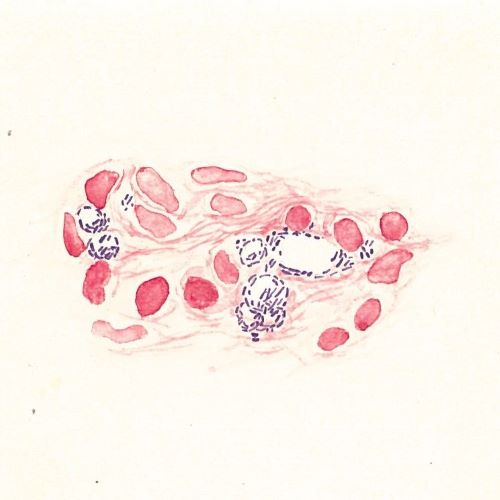

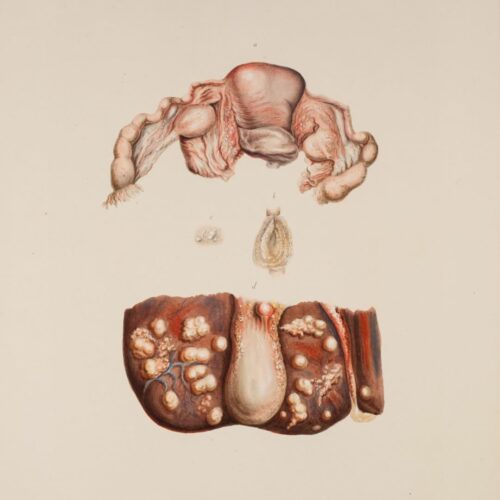

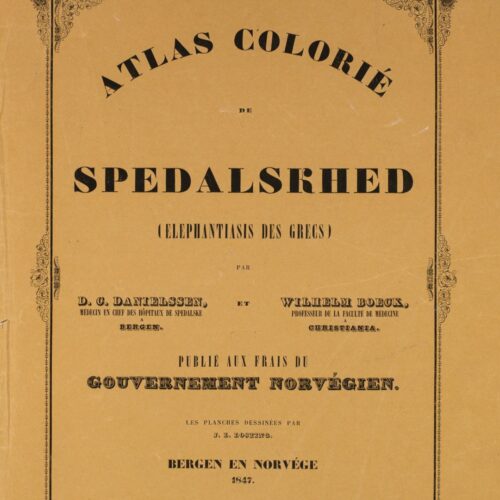

‘Atlas Colorié de Spedalskhed’

The atlas accompanied the book ‘On Leprosy’ and contains 24 colour plates depicting the external characteristics of the disease as observed in the residents at St. Jørgen’s Hospital in the 1840s. The watercolours were painted by the artist and lithographer Johan Ludvig Losting and engraved at Prahl’s lithographic workshop in Bergen.

The journal ‘Medicinsk Revue’.

This Norwegian medical journal was established by four doctors in Bergen in 1884, including Eduard Bøckmann and Gerhard Armauer Hansen. The journal contained some original works by Norwegian scientists but was largely based on the reproduction of summaries of international research. The scientific library at Lungegård Hospital played an important role.

The Leprosy Registry

The leprosy registry contains information about 8,231 people with leprosy in Norway, starting in 1856 until the last cases were diagnosed in the 1950s.

The registry was started on the initiative of Ove Guldberg Høegh (1814–1863) who was the first person to become ‘Chief Medical Officer for Leprosy’ in 1854. This was a government office established to dedicate one person to combat leprosy and propose measures to eradicate the disease. He ensured that a system of national counts, later to become the foundation of what was later known as the leprosy registry, was established by royal decree in 1856.

Collection and analysing information about everyone diagnosed with leprosy in Norway was a major undertaking, but it provided new knowledge that could be applied in several different ways. The registry became the health authorities’ most valuable tool for attempting to control the spread of the disease. The data allowed them to track the progression and regression of the disease in different geographical areas and both plan and assess the effect of measures implemented.

The analyses of the registry were Hansen’s primary argument to convince physicians and authorities that leprosy was an infectious disease. Using data from the registry, he could prove that isolating those diagnosed with leprosy had an effect, and this was given considerable weight in the debate about the disease’s cause and what measures were appropriate and necessary to eradicate it.

The leprosy registry is considered to be the first ever national patient registry, and more were to follow. The utilisation of the data from the registry showed the important role health registries play in epidemiological research and public health.

The leprosy registry

Collecting and analysing information about everyone who had leprosy in Norway was time-consuming, both for district medical officers and the Chief Medical Officer for Leprosy, but it provided new and valuable knowledge for health authorities and medical experts. The Leprosy Registry is considered the first ever national patient registry. It served as a model for other registries and illustrates the important role that health registries play in epidemiological research and public health.

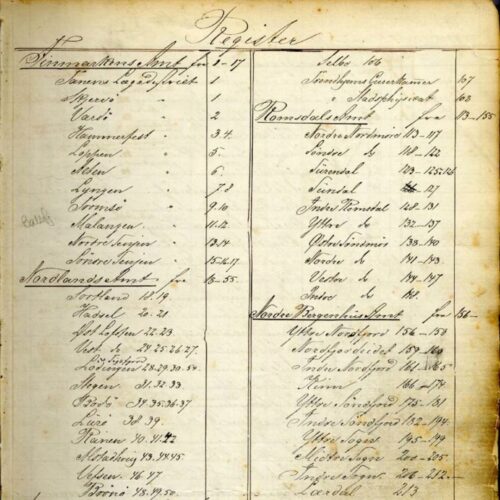

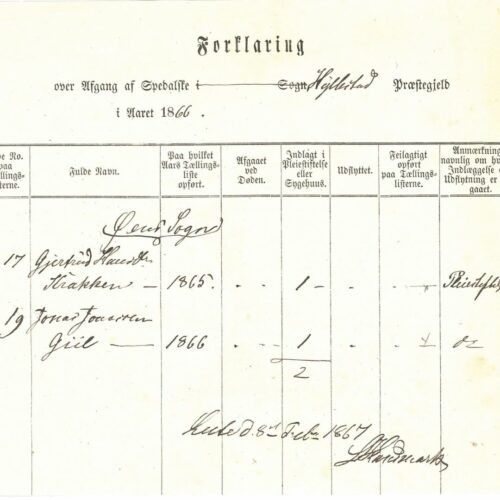

System of registration

District Medical Officers, aided by local pastors and health commissions, were to create detailed overviews of everyone afflicted with leprosy. There were several different forms for registering information, containing a number of columns that had to be filled in. Reports from across the country were then added to and organised in central registries, which were used by the Chief Medical Officer to produce and publish statistical material.

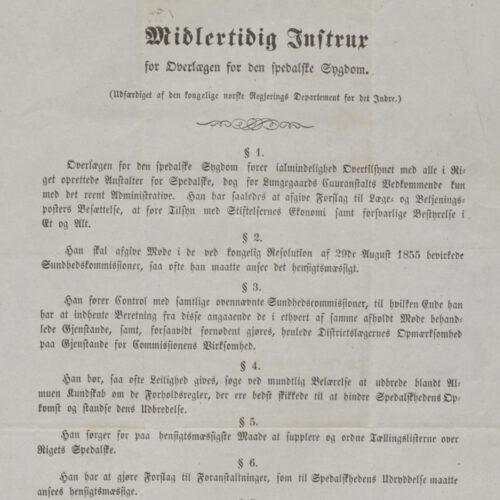

‘The Chief Medical Officer for Leprosy’

The Chief Medical Officer was to work on combating leprosy and propose measures that could help eradicate the disease. Central duties included the operation of the state care institutions and the administration and analyses of the leprosy registry data. A total of five doctors held the office between 1854 and 1957, ensuring continuity of the state’s efforts to combat the disease.

The registry’s significance

The registry became an important tool in the health authorities’ efforts to limit the spread of the disease, making it possible to continuously monitor the prevalence in different geographical areas and to observe the effect of the measures implemented. Analyses of the registry’s data were also pivotal to Hansen’s argument that the disease was infectious and that isolation was a recommended measure.

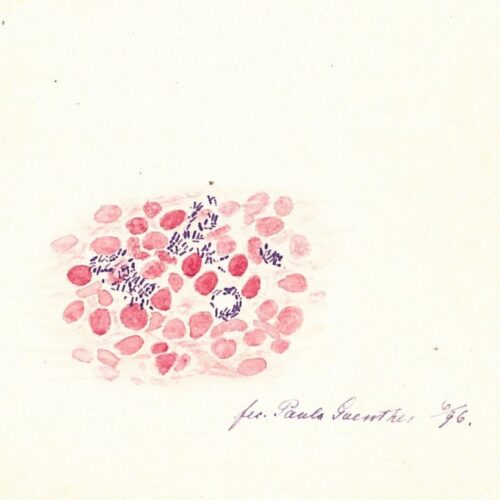

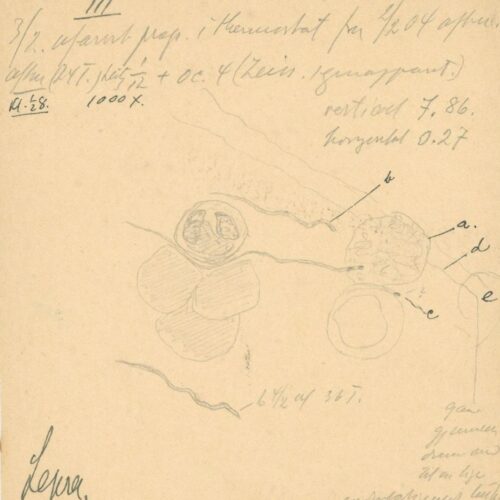

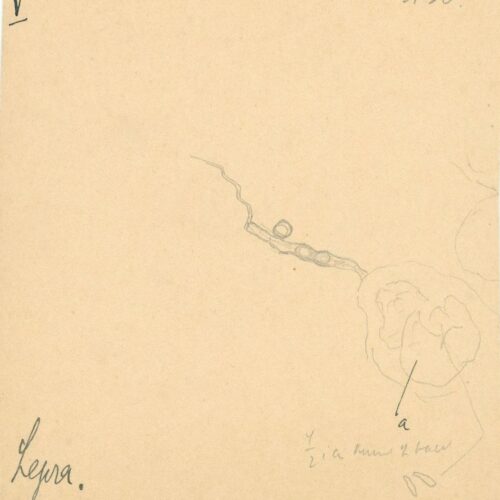

The discovery of the bacteria

On the evening of the 28 February 1873, the Bergen doctor Gerhard Henrik Armauer Hansen (1841–1912) discovered the leprosy bacteria – Mycobacterium leprae.

The discovery of the leprosy bacteria was a scientific breakthrough. One can wonder at how such a breakthrough could happen in such a small city on the edge of the world, but at that time, the doctors in Bergen were at forefront of leprosy research. They were part of an international community that shared knowledge and experience with each other. Hansen could draw from previous and contemporary scientific research, as well as the advancements in scientific and technological developments of his time. Modern microscopes enabled him to observe microorganisms, and he maintained correspondence with other leading scientists within the emerging field of microbiology. Additionally, he could use data from the National Leprosy Registry to substantiate the theory that leprosy was infectious.

It would still take time from when the bacteria was identified until it became generally accepted that it was the cause of leprosy, and that leprosy consequently was an infectious disease. The discovery was a prerequisite to the disease being conclusively diagnosed and eventually treated and cured. Hansen’s work would have consequences for millions of people the world over, both positive and negative.

Identifying an infectious agent

Even before Hansen was employed as a physician at several leprosy hospitals in 1868, he was already convinced that the disease was caused by an infectious agent. If that was the case, the agent should be detectable in diseased organisms. The question remained, however, of where precisely in the patient he should look and what type of infectious agent he should be trying to find.

Making the invisible visible

The microscope technology of the day made it possible to search for an infectious agent. Microscopes had significantly improved and researchers had gained a clearer understanding of microorganisms. This laid the groundwork for developing scientific principles for proving the link between microorganisms and disease.

The search for evidence

In order to prove that bacteria was the cause of leprosy, it was not enough to merely observe them under a microscope. It was also necessary to observe them causing the disease. In November 1879, Hansen summoned the patient Kari Nilsdatter Spidsøen into his office at Pleiestiftelsen Hospital. Against her will, he inserted leprosy-infected material into the conjunctiva of her eye.

Trial, verdict and ethics

Armauer Hansen’s experiment on Kari Nilsdatter had legal consequences. He was charged with bodily harm, but he was only convicted of abuse of office. He lost his position as physician at Pleiestiftelsen Hospital but remained in his post as Chief Medical Officer for Leprosy. Although the verdict has since been considered groundbreaking for patients’ rights, it was not widely discussed publicly in its day.

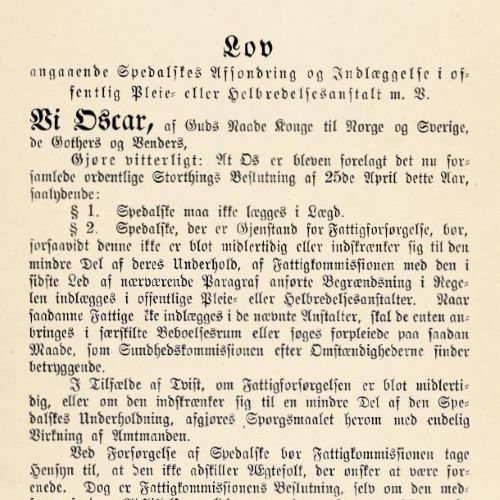

Legislation and isolation

‘The Act concerning the Isolation of Persons with Leprosy and their Hospitalisation in Public Nursing and Curative Facilities etc.’ was enacted in 1885. It was the second act to specifically address leprosy, but the first to apply to all citizens. The act was the result of analyses of the leprosy registry showing that isolation contributed to fewer new cases of leprosy.

The act sparked debate because it enabled forced hospitalisation, but this was only possible if individuals did not adhere to guidelines for home isolation and thus posed a risk of infection to those around them. Many with leprosy remained living closely integrated with their local communities, and it was not until about 1900 that more people with leprosy were staying in hospitals than living at home.

Leprosy legislation

A new leprosy act from 1885 was the first Norwegian act to permit the use of force in relation to the chronically ill. This provoked debate, even though force could only be used in instances where it was deemed necessary to prevent transmission. People affected by leprosy could continue to live at home on the condition that they lived ‘in satisfactory isolation from their family and surroundings’.

Humane legislation?

There was lively debate about the new legislation. Many believed the act was too strict and protested against it ‘in the name of humanity’. Its most critical opponents alleged the act likened those affected by leprosy to convicts. Hansen, who had formulated the principles behind the act, made the case that one could not only consider those who had leprosy, but that they also had a duty to protect their fellow citizens.

Coercion or education?

The coercion clause was not used to any great extent, but the act had a potential educative effect on those who were living at home. They could remain at home on the condition that they ensured a safe distance from others. If they exercised a greater degree of caution in their contact with others to avoid hospitalisation, this would help reduce the risk of transmission.

Isolation – at home or in hospital

Although Norway was seen as a role model when it came to using isolation as a means of combating the disease, at no point were all those registered with the disease admitted to hospitals or care institutions. It wasn’t until some point between 1890 and 1900 that more people with leprosy were staying in hospitals than living at home in their local communities.

Norway and the world

The leprosy act – a role model?

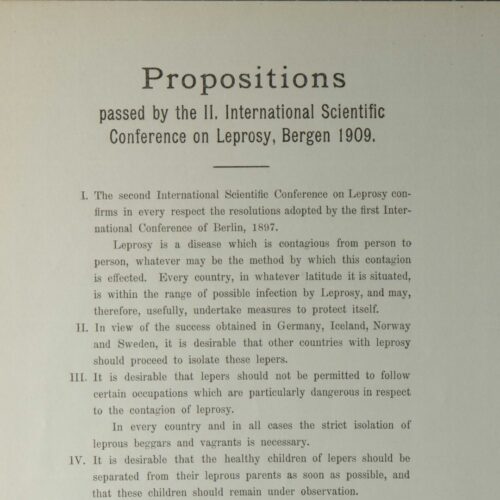

The Norwegian legislation garnered world-wide interest and to some extent inspired much stricter legislation in other countries. Debates and resolutions at the International Leprosy Conferences in Berlin in 1897 and in Bergen in 1909 led to an agreement to recommend compulsory registration and isolation of those affected by leprosy. But was this not based on a somewhat simplistic view?

The Leprosy Conference in Bergen

The second International Leprosy Conference was held in Bergen in August 1909. For four days, almost 180 participants from 30 countries and four continents came together, including numerous prominent medical figures of the time. The conference’s proceedings were printed in three volumes. They show that Armauer Hansen’s argument that leprosy was an infectious disease had gained traction all over the world.