Food and cooking at St. Jørgen’s

The residents of St. Jørgen’s Hospital shared common kitchens. There were separate kitchens for the residents of the main ward, the smaller ward and the ‘healthy ward’. During most of the 18th and 19th centuries, the residents did their own cooking. In the second half of the 19th century, the hospital’s finances improved and more staff were employed. At that time, cooking for the residents was one of the maid’s many tasks.

The hospital also received donations in the form of meat and butter, and they also had milk from the hospital’s cows. This was distributed among all the residents.

Dietary lists

The first statute for St. Jørgen’s Hospital from 1545 did not contain any provisions about what residents were to eat or the hospital providing food or money for food. However, the statute from the 17th century stipulated the kind of food residents were to be given based on a dietary list.

In the statute from 1617, it was decided what food the residents were to receive each day. Examples of this include ‘Bergenfisk (dried cod) and flour soup’ on Mondays, and one slice of meat and meal soup on Thursdays. They were also given bread and butter.

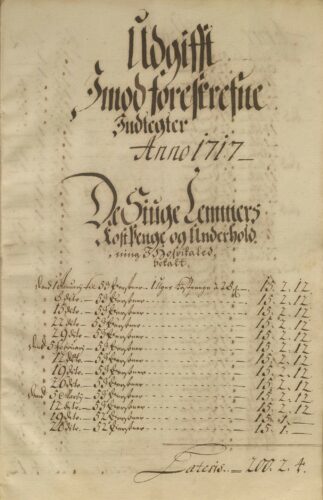

In the new statute from 1654, the arrangement was a bit different. The number of residents had significantly increased, which in turn worsened the hospital’s finances. In order to save money until the hospital regained stability, it was decided that residents would partially receive food and partially receive money for food, once a week on Saturdays. A certain amount of bread, rye flour, butter and smoked mutton was provided to them. In addition, they received money for fresh meat and fish, herring, peas, coarse rye flour and beer. Below are both dietary lists with the kind of food residents were to eat each day or week.

Food allowance

In 1691, food allowances were also introduced as a saving measure. From then on, residents received money and were responsible for obtaining and preparing their own meals. Those who were bedridden or could not cook for themselves had to rely on assistance from other residents. This continued throughout the 18th century and for large parts of the 19th century. The amount of money remained the same, despite inflation. The weekly food allowance was not increased until the late 19th century. One of the reasons residents were granted permission to produce and sell shoes in the mid-18th century was that the weekly food allowance was insufficient.

Diet in the 1840s

In a report from 1841, the physician Danielssen describes the chaos in the kitchen when all the residents cooked simultaneously. The residents’ diet does not appear very different from that of the 17th century. The residents eat a lot of fresh, salted, and cured fish, as well as gammelost (‘old cheese’ made from sour milk) and mysost (a sweet, brown cheese). Those who could afford it often had a hot breakfast of either meat, fish or meat soup. Somewhat disapprovingly, Danielssen describes the residents drinking coffee in the morning – and not just a cup, but a proper bowlful. Furthermore, they drank beer, something he believed caused great harm.

Danielssen was critical of the residents’ diet and of the fact that residents prepared their own food. In his opinion, this led to them buying cheap and not necessarily nutritious food. It does appear, however, that many of the residents appreciated having the ability to choose what they ate.

The Regional State Archives of Bergen.

Photo: Olav Espevoll © University Museum of Bergen.

Photo: Bergen City Museum.

Photo: Ingfrid Bækken.

Photo: Bergen City Museum.