Statutes of St. Jørgen’s Hospital

The statute for St. Jørgen’s Hospital was a set of rules issued by the state regarding the use and management of funds set aside for a specific purpose. Such statutes particularly applied to charitable foundations, such as St. Jørgen’s, that have a social purpose and use their funds for the good of certain people or purposes. The statute describes how the foundation is to be operated and how the funds are to be used.

There are known to be three different statutes for St. Jørgen’s Hospital, all from after the Reformation, from 1545, 1617 and 1654. Each contains provisions about how the hospital was to be run and so tell us how daily life was supposed to be at the hospital. However, the reality may not always have matched the provisions in the statutes. When supplemented with other sources, the statutes can nonetheless tell us a great deal about the history of St. Jørgen’s Hospital’s, how it was run and what life was like there.

The oldest statute of St. Jørgen’s Hospital, 24 April 1545

The oldest known statute of St. Jørgen’s Hospital was issued by King Christian III on 24 April 1545, and it tells us how the hospital was to be run after the Reformation. It’s provisions are influenced by the what are known as the Ribe articles from 1542, which regulated the church in Denmark-Norway after the Reformation. The Ribe articles had specific provisions about hospitals and St. Jørgen’s land holdings.

In the statute, the foundation is converted into a royal foundation, meaning that it would be under state authority but its funds would still belong to the foundation. The representatives of the state and the city were to decide who should be admitted to the hospital. These representatives were the city’s mayor and council, as well as the superintendent of Bergen’s diocese, who was the King’s highest clerical official in the diocese (somewhat equivalent to a bishop before the Reformation). Together with the governor of Bergenhus fortress, they would appoint the foundation’s superintendent, who was to submit the hospital accounts to them and account for the operation of the hospital. He was to be a person ‘who is God-fearing and who will be faithful to the Poor’.

The hospital was turned into a general hospital for ‘poor, weak and sick people’, although people with leprosy are not specifically mentioned. This is a result of the Ribe articles, which stipulate that people with leprosy should not have their own institutions but should be admitted to general hospitals. The reason for this was probably that cases of the disease were declining in Denmark, although there were still many people with leprosy in Norway. Based on other accounts, it seems that many of the hospital’s residents also had leprosy after 1545.

The statute also granted the hospital all the property, goods, interests and rights that had belonged to Selje monastery before the Reformation, as the King followed through on a promise he had previously made. This included around 175 farms in Western Norway and became the financial foundation for running the hospital in the following centuries.

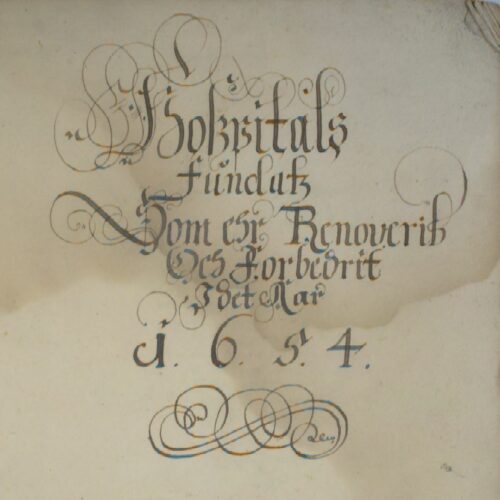

St. Jørgen’s new statute in 1654

In 1654, a new statute was established for St. Jørgen’s Hospital. It provides a rich source of information about the hospital in the 17th-century and reflects many of the challenges faced by residents and the administration at the time. The statute includes detailed provisions for admission, food provision, rules of conduct, staff wages and the allocation of donations. The principles laid down in this statute were largely continued until the 19th century.

The superintendent must be a God-fearing and pious man living ‘a good, pious and virtuous life’, who was not seeking personal profit. Perhaps the hospital previously had a problem with superintendents who tried to use their position for their own good. The superintendent’s duties included keeping accounts for the hospital and distributing food allowances to the residents.

The residents were to live a godly life and be ‘pious, pleasant, peaceable and quiet’. They were to thank God with prayers and hymns in the morning and evening. They should work if able and were not to ‘run out into the City’ but stay within the hospital’s boundaries. If they refused to work, they were to be banished, and if they did not behave, they would first be given a warning, and if they failed to improve they would be expelled.

The statutes also stipulated what kind of food the residents were given and how often. It also stated that those who cared for the sick should be paid, that the hospital’s meadow and its cattle should be for the residents’ ‘necessity’, and also contained provisions about the chaplain, his wages and his work. Among other things, the chaplain was to ‘comfort the consciences of the sick’ at least once a week.

The statute describes many aspects of the hospital’s operation and daily routines, although the extent to which life at the hospital corresponded with the provisions in the statute is unknown.

The Regional State Archives of Bergen.