The smell at the hospital

When reading older descriptions of the hospital, the smell is one of the things people tend to notice. It must have been a significant part of the experience when visiting the hospital until well into the 19th century. The smell must also have been large part of daily life for those living at the hospital, although they probably became accustomed to it.

The city physician Büchner, who came to Bergen from Germany in 1758, is described as retching at the stench of the patient’s wounds and their other emanations. He could only bear to be in the hospital if he had a sponge soaked in vinegar over his nose and mouth. Even with the constant smoke from juniper berries, he found the air in the hospital nauseating.

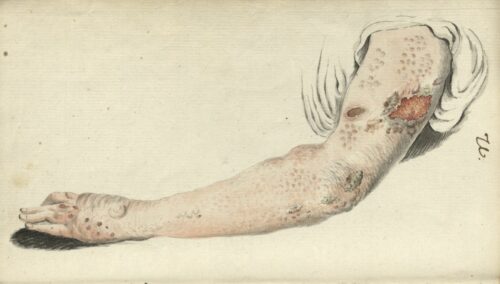

The Danish natural historian Johan Christian Fabricius, who visited Jørgen’s Hospital in 1778, describes that a sharp, foul-smelling liquid emanated from the patients’ nodules when they scratched their itching skin. It seems they would do this frequently, as he describes the itching as intolerable.

When the hospital’s doctor, Dr Danielssen, submitted a report to the ministry in 1842, he emphasised how stuffy the air was in the patients’ rooms, since they were almost never aired. He could hardly spend time there without letting in some fresh air. One thing was the smell of the patients, but the food they kept in their rooms also added to the smell. The residents kept cheese, milk and fish in their rooms. The brigade medical officer Jens Johan Hjort described the same conditions ten years earlier. Because of all the foods in the rooms, such as salted fish and the like, there was always a ‘strong stench’ when the doors were closed.

The number of such reports decrease from the latter half of the 19th century. Perhaps the level of hygiene improved after this time, but ventilation was apparently also installed in the main ward in the 1880s.

Walking around the peaceful, clean and tidy rooms at St. Jørgen’s Hospital today, it’s difficult to imagine how the conditions used to be. Two-hundred years ago, the main ward and the small cells were rank and stuffy, but they were also full of life, with around 80 residents going about their daily lives, work and dealing with their illness.

Foto: © Image courtesy of the Hagströmer Medico-Historical Library, Karolinska Institutet.

Photo: Bergen City Museum.

Photo: Bergen City Museum.