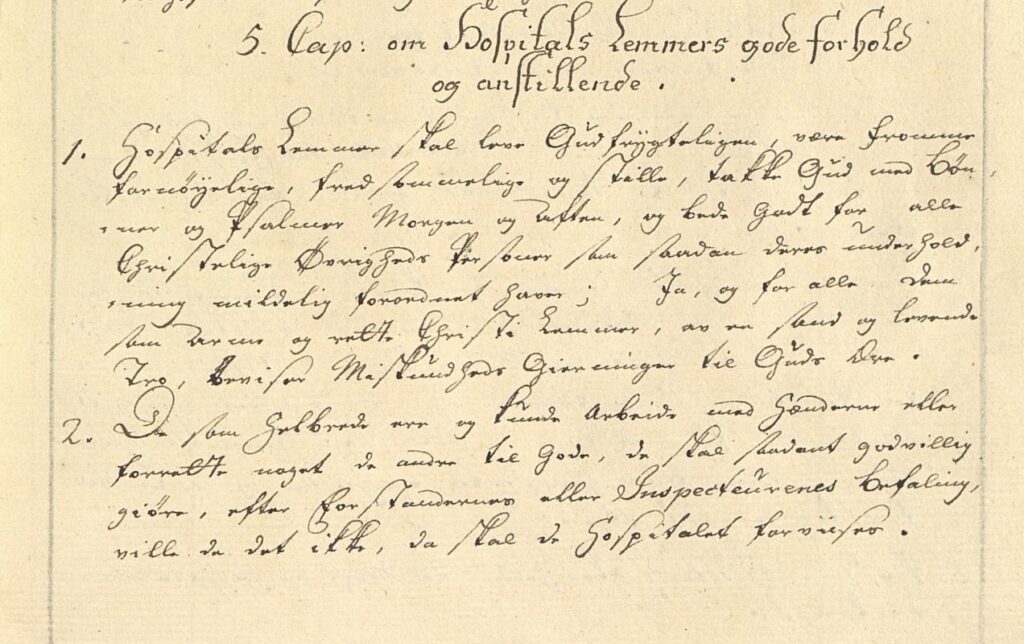

The residents’ work at St. Jørgen’s Hospital

Work was an important part of daily life at St. Jørgen’s Hospital. Ever since the first statutes were created in 1617, residents were expected to work. In the two sets of statutes that date from the 17th century, those who are able to work are obliged to do so. However, the statutes say nothing about whether the residents could keep the income from the work, which was the normal practice in the 18th and 19th centuries. At that time, the sale of self-produced goods was an important addition to the weekly subsistence allowance.

In his account from 1764, Hilbrandt Meyer states that the men made bowls, buckets, tubs and birdcages, as well as shoes for farmers and others, while the women washed clothes, and spun and plied thread and yarn. He describes the residents as hard-working and cheerful, and pleased with what they produced.

Hospital chaplain Welhaven also described the patients as hard-working. He wrote in his account of the hospital in 1816, ‘in relation to their strength, leprosy patients are industrious people.’ He said that the women spun flax, tow, hemp and wool, they sewed, knitted and wove wool bands. The men made boots for fishermen and shoes for farmers (probably clogs), made fishing nets and tools, matches, bowls and buckets.

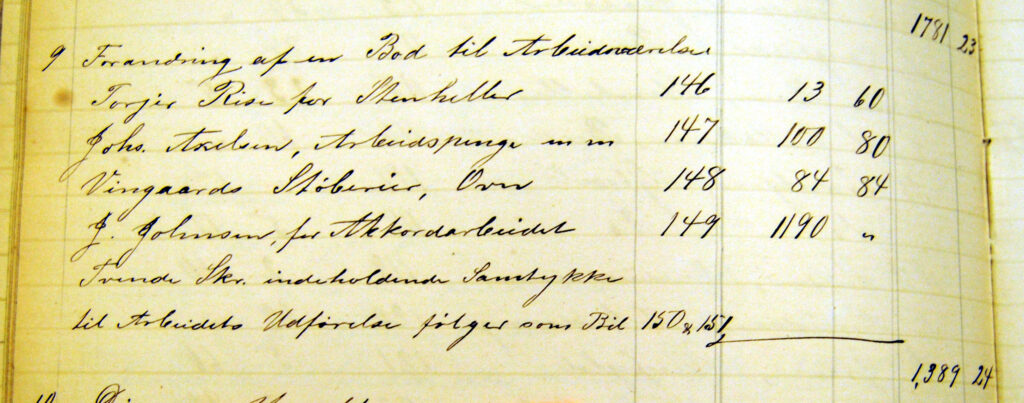

The work was carried out in the large common areas at the hospital, and probably caused a lot of dust and noise. In the 1870s, a workroom was set up in what used to be the woodshed next to the barn. At the end of the 19th century, this room is referred to as a carpentry workshop, while one of the rooms in the small outbuilding facing Kong Oscars gate behind the main building was referred to as a spinning room. This suggests that women and men worked separately at that time.

The residents also engaged in farm work at the hospital until the beginning of the 19th century.

Bergen City Archives.

Bergen City Archives.