Observations of Leprosy Patients in St. Jørgen’s Hospital in Bergen in 1841.

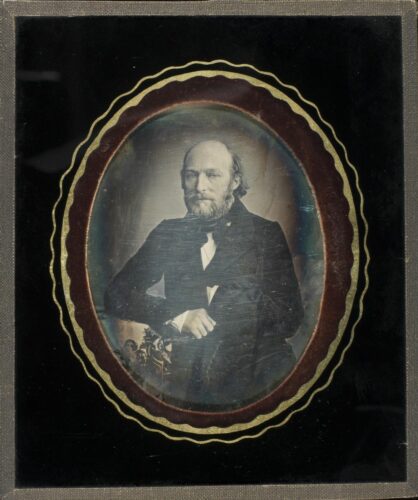

By corps medical officer D. C. Danielssen in Bergen.

(…)

In the past year, there have been 155 individuals in the hospital, of whom 79 are women and 76 men. (…)

As far as I have observed, there are only two forms of the disease among the pastients who have been in the hospital during the past year, namely Elephantiasis ’anæsthos’ and Elephantiasis tuberculosa. The first is characterised by a sallow and somewhat violet skin colour, a dry and loose skin, facial twitches, ectropion, a diminished and, in extreme cases, complete lack of sensation in all the soft tissues of the extremities, face and roughly the lower half of the body, a diminished warmth of life, ulcerations that break through the skin, and finally tooth decay and necrosis, by which entire joints are eaten away. Life can rightly be said to be extinguished in the parts mentioned; for limbs are amputated without the sick feeling the slightest pain, and not even knowing that amputation has begun until he hears the cut of the saw; and it is not uncommon for these sick people, who almost constantly complain of cold, to subject themselves to burns in the third degree when warming themselves by the stove with their hands behind their backs. They are first made aware of this by the smell of burning in the room or being told by other sick people present.

(…)

St. Jørgen’s hospital has virtually been designated a care facility and is, as such, tolerable enough. It is in a low and swampy location, and is built in a rather old style, without any visible regard for the fact that it is to be inhabited by the sick. It has two buildings where the sick reside. The largest is two-storeys and comprises two wards, which occupy both floors and are separated by two large kitchens. In each ward there is a gallery, and both above and below it are small cells, which have a door either to the gallery or to the common area. In the largest ward, which constitutes the eastern wing, there are 40 such cells, 20 below and 20 above. This ward and all the cells are heated by two rather large stoves, standing approximately in the middle of the room. Each cell is 3 ells and 2 inches long, 3 ells and 9 ½ inches wide, and 4 ells and 4 inches high, and has a small window that is just opposite the door, except for 8 of them, which are completely dark. The common area is a joint workroom for those who live in these 40 cells, and has a door adjacent to the courtyard and one that connects to one of the kitchens. Such a cell has two beds and is inhabited by two people, who store therein various kinds of foodstuffs, such as butter, cheese, milk, fish, etc . In the left wing there is a similar ward, which has only 16 cells of the aforementioned size, one of which is occupied by the doctor. This ward and cells are heated by one stove and is also directly connected to the other kitchen. The smallest building, which lies to the south, also consists of two rooms, which are separated by a kitchen through which you enter. There is no gallery here and each room has 8 cells.

This unsuitable building design, with an arrangement housing so many sick people, makes no insignificant contribution to their condition. In the winter, those who occupy the galleries regularly have temperatures six to eight degrees higher than those who live below, and in the summer the difference varies between two and four degrees, which results in a strong, oppressive heat in the galleries, making breathing difficult; and as the atmosphere there is more impure, more mephitic, if I may call it so, the oxidation of the blood is reduced. This even goes so far as to suggest that those whose chests are filled with tubercles, and so have difficulty filling their lungs with air, are far better off, breathe much more easily, and indeed have a less bluish appearance, when they have spent time below. If, as some physicians have asserted, people affected by leprosy thrived and were happy to live in a foul atmosphere, and could not bear to breathe clean air, then it must be admitted that St. Jørgen’s Hospital would be exceedingly comfortable for that kind of sick person. However, experience shows that their sickness and suffering worsens, and new sickness arises, when they spend time in a room where the atmosphere is hot and less pure, as is the case with the hospital’s cells. It was undoubtedly desirable that their quarters be less perilous. The arrangement of the cells is as unsuitable as that of the gallery. When the door is kept shut, as is regularly the case when they are in bed, it is clear that the stench of two individuals in such a small space, in conjunction with the stench of the various victuals stored therein, must very quickly taint the confined atmosphere. Indeed, it is at times so impure that it is impossible for me to spend even a short time there, before I have to let in more fresh air. The fact that the doors of the common areas turn right into the kitchens also has many disadvantages; the smell of food, smoke, and other impurities is the immediate consequence.

But what is even worse and more harmful about the arrangement is that no proper economy is maintained. Every resident has four shillings daily, and a share of the considerable gifts, both of money and victuals, which are sent to the hospital. With this he must procure clothing, sanitation, care, and food, and up until last year even had to pay taxes to the officers of the Church. Although the gifts are considerable, they have never been sufficient to provide board and lodging for the sick, devoid of nutritional care, which has led them to run various kinds of affairs, which must be regarded as harmful, inasmuch as they are associated with many impurities. Every resident takes care of his own housekeeping, buys the food he needs, and looks as much at what is cheap as at what tickles the palate. They made much of meat and fish, fresh, salted and cured; and as this consists of cured meat and pork, different kinds of cheeses, this also contributes considerably to the fact that their diet is far from appropriate considering their disease. Coffee is drunk in the morning, and not just a cup, but a proper bowlful, and those whose resources are better also have a hot breakfast, consisting of meat, fish, meat soup, or other such things.

At nine o’clock in the morning the preparations for dinner begin, and the kitchen then turns into a real pigsty, which is understandable, given that every sick person cooks his own meal. During this time, anything from 100 to 135 pots are on the go, in which the most different things are found, and as soon as these are finished, they are replaced by almost as many coffee pots. Beer is a common drink, and this also causes considerable harm. It is therefore easy to see when the Christmas beer has all but been drunk up, for the tubercles are then more prominent than ever before, their skin burns, and pitiful laments of pain are heard; but to convince them that the beer is to blame is just as difficult as trying to curtail their drinking. Excessive drinking of liquor is no longer an issue; but at times they take a dram when they have been out in the city and are wet or cold, and consider it necessary and beneficial. I have not succeeded in convincing them of its harmfulness. Instead of liquor, the women enjoy mead and wine, and they regard these things as a necessary restorative. There is no control, the sick can enjoy what they desire, both of food and drink, they can go out into any part of the city and stroll around at any time, except at night or when they are attacked by some acute disease. I kindly ask them to refrain from their usual diet, and often spend a long time using all my powers of persuasion to urge them to use medicine, and I consider it a victory when I occasionally succeed. Confidence in medical care was utterly shattered when I took over the affairs of the hospital, and it could not have been any worse. I wish and hope that it has somewhat improved.

In such circumstances, where the facility suffers from so many essential shortcomings, I found it both useless and wrong, in the long run, to attempt to cure the sick, and all the more so, as in so doing, I aroused a general dislike among the patients, and this made me very quickly cease any attempt to cure, and to proceed instead to palliate.

There is hardly any disease more abominable than leprosy, nor is anyone more pitiful than the poor who are attacked by it. They are ostracised from their dearest surroundings, and arouse horror and loathing among their fellow men; they see their prime of life, healthy appearance and happiest hopes go to ruin, and they drag their miserable lives around in an uninterrupted succession of torment, without the slightest glimmer of hope of ever being freed. When they are admitted to St. Jørgen’s Hospital, to the State they are dead citizens who have marched a long way on their road to the grave.