Dr Danielssen – an eternal quest for a cure

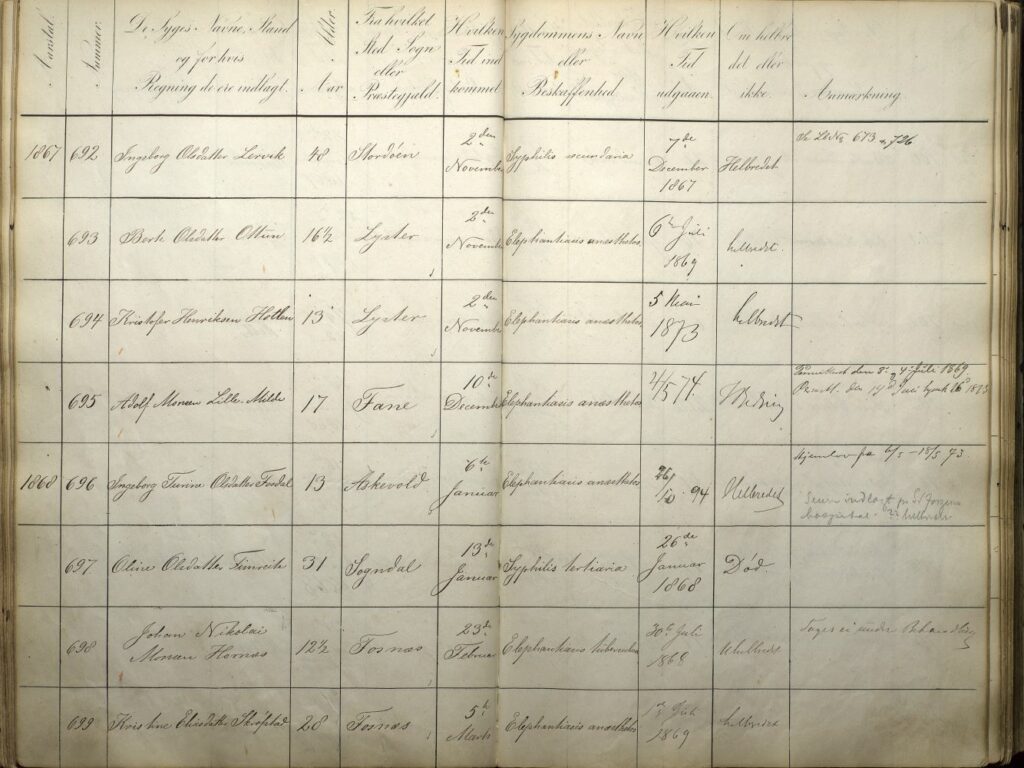

Throughout his 40 years as a doctor at Lungegård Hospital, the head physician Danielssen was on an eternal quest to find for a cure for leprosy. This is reflected several times in the triennial reports he wrote for the hospital. In 1862, he pointed out that he could not for one moment give up the belief in the ‘curability of leprosy.’ The simplest thing would have been to say that nothing could be done about the disease, other than provide the sick with good dwellings, food and clothing. However, he believed that this point of view was ‘unworthy of the human spirit’ and, for a physician and scientist, it was to give up on oneself.

Ten years later, he still believed that there had to be a remedy that could cure leprosy, even after decades of testing out a range of medication that had proved to be ineffective, or even harmful. He stated that he considered it his duty to search for a cure for the disease, and so seized every opportunity to test medication that others claimed to have used successfully.

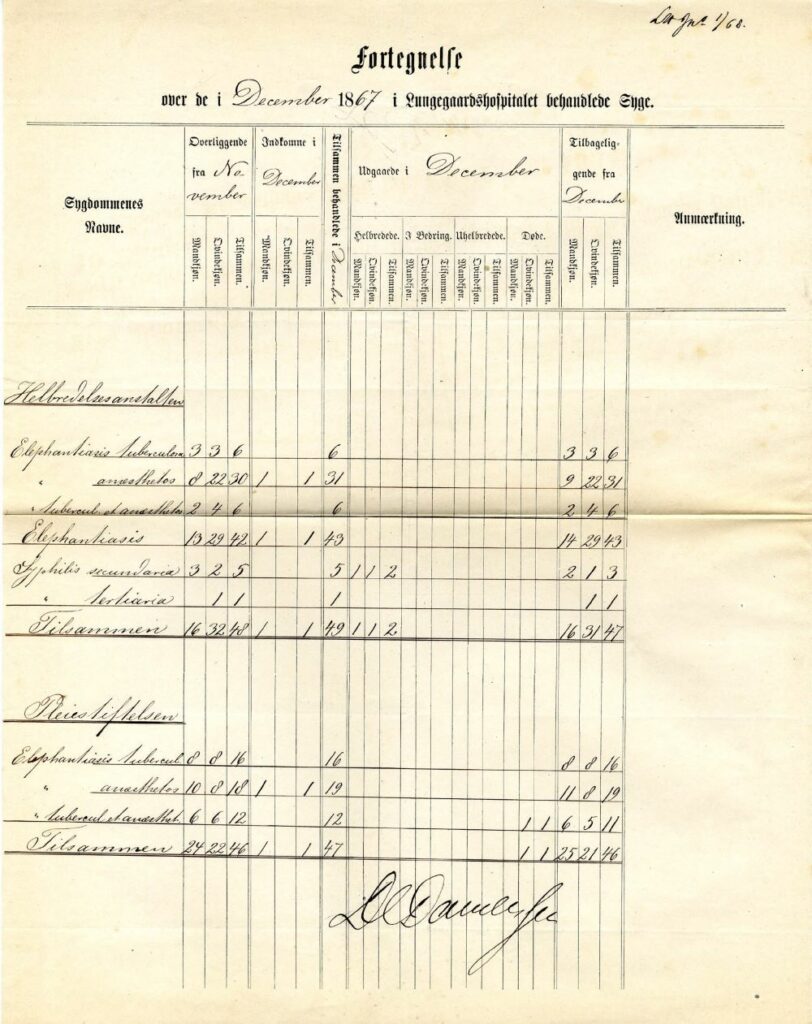

The many triennial reports, which were published in the medical journal Norsk Magazin for Lægevidenskaben, bear witness to this. He tried everything he came across and made precise records of the effects of the different forms of medication. He had oils, ointments and powders shipped from a variety of sources all over the world and keep abreast of what treatments were being tested elsewhere. He often took a sceptical view of the results others claimed to have achieved, but nevertheless always tried out the medication just to be sure.

What about the patients? Were they asked if they wanted to take part in all the trials, or were they simply given new medication without knowing what they were involved in? Danielssen writes nothing about this, and reading through the different reports, you have to wonder. However, in one instance, we have an answer. When he trialled gurjan oil in 1874, the treatment was only tested on the men because the women in the hospital did not want to participate in the experiment until they saw how the men fared. In that instance, it is clear that the patients were asked and had refused, a decision that was respected.

We learn that on another occasion, an experiment was discontinued because both Danielssen and the patients were tired of having to apply medication to the skin. This may also be an indication that the patients knew they were part of a trial. Although there are only a few notes about this, it indicates that patients may have been informed of the trials and could decide whether they wanted to participate.

The University of Bergen Library.

The Regional State Archive of Bergen.

Bergen City Archives.