Hope of recovery?

Although Pleiestiftelsen was originally intended primarily as a care facility, observations and trials were still carried out. As early as 1860, one patient room was reserved for men and one for women, where a total of 14 patients were selected who were considered ‘fit to undergo curative trials.’ These were young people who had not had the disease very long, and who were therefore thought to have the best chance of being cured.

Head Physician Løberg believed that, if the disease had recently been diagnosed, its progression could be stopped, or perhaps even cured, as long as patients abided by strict control and a way of life that was ‘in accordance with the health rules’. What he primarily meant by this was being extremely strict with cleanliness, frequent bathing, healthy air, avoiding colds, wearing clothes suitable for the season and woollen garments next to the skin, and ensuring a healthy diet, regular exercise in the fresh air and suitable work.

The annual reports reference certain patients who were discharged because they were considered cured, or because they didn’t have leprosy after all. In 1873, patient no. 355 Johannes Tollefsen Mehus was discharged as cured. He was hospitalised in 1858 with his parents. He was only three years old at the time and his symptoms were weak. He was around 18 years old when he was discharged, and was described as ‘well-nourished and strong’ and without ‘diagnosable signs of leprosy’. As with several other hospitals, patients discharged as cured often returned after some time with new symptoms, but it is not known what happened to Johannes Tollefsen Mehus.

From 1895, Pleiestiftelsen was defined as a sanatorium. A distinction was made between the curative and the care department, and there were always far fewer patients in the curative department. The annual reports include many descriptions of remedies that were tried without success. In 1901, Lie concluded that for the vast majority of patients ‘leprosy runs its course despite all treatment,’ and that he had not seen any cases where he was convinced a treatment had done any harm, but he had also not seen many cases where treatment had been particularly beneficial. This would all change in 1947, with the advent of the first effective medicines.

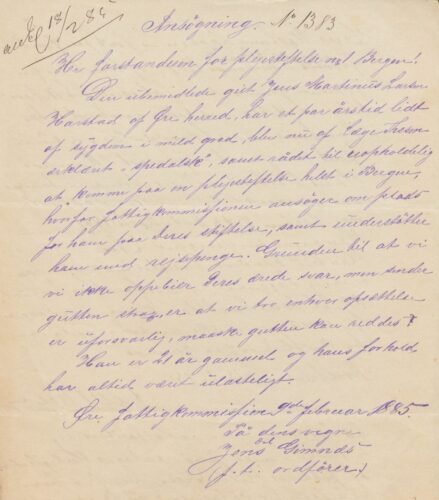

The Regional State Archives of Bergen.