A genetic blood disorder?

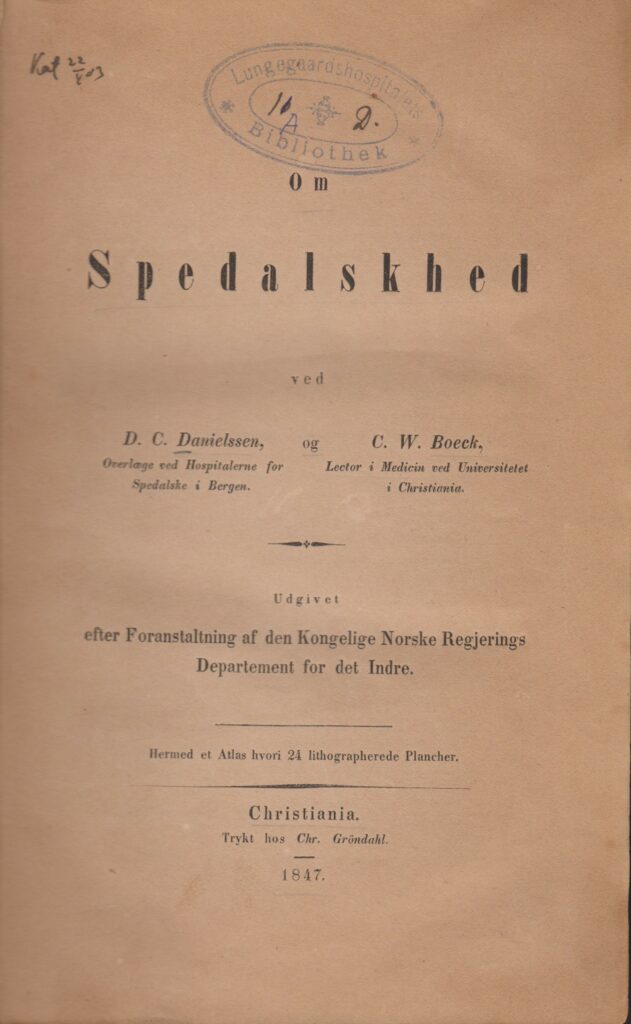

After the publication of the book ‘On Leprosy’ by Daniel C. Danielssen and Carl Wilhelm Boeck, the spotlight was firmly directed towards heredity. When these physicians began their research in the 1840s, they both placed great emphasis on describing leprosy as a specific disease, not just as a general condition that affected malnourished and unhygienic Norwegian fishermen and farmers. There was still a great deal of uncertainty about the actual cause of the disease.

Danielssen had observed that the majority of residents at St. Jørgen’s Hospital had family members or other relatives with the same disease, and that often, leprosy had been present for several generations. There was little to indicate that the disease was infectious, as the healthy residents and staff at St. Jørgen’s did not become ill.

In 1844, Danielssen inoculated himself using nodules from patients, and several months later, he tried the same thing using blood. The experiments were repeated both on himself and on other employees of St. Jørgen’s, and in the period between 1856 and 1858, they were also conducted on several physicians and other employees at Lungegård Hospital. None of the participants of the experiments showed any signs of developing leprosy.

Danielssen’s conclusion was that leprosy was a hereditary blood disorder. He claimed that the disease could be acquired through a reckless lifestyle, but that it was primarily transferred from parents to children through heredity. He argued that more patients should be admitted to hospitals, not to prevent general transmission, but to curb sexual contact and thereby prevent hereditary transmission.