‘Chief Medical Officer for Leprosy’

The position of ‘Chief Medical Officer for Leprosy’ was established in 1854. The medical officer was tasked with combating the spread of the disease and proposing measures that could contribute to its eradication. The first person appointed to the position was Ove Guldberg Høegh. It soon became apparent that the workload was too extensive for one person, and in 1858, the position was split into two positions for a northern and southern district. Høegh was given responsibility for the northern district and was based in Reitgjerdet in Trondheim, while Timandus Løberg held the position in the southern district in Bergen. From 1863, it was again reverted to a single position, based in Bergen.

In addition to Høegh (1854–1863) and Løberg (1858–1875), three other physicians held this position – Gerhard Armauer Hansen (1875–1912), Hans Peter Lie (1912–1935), and Reidar Melsom (1935–1957). All five served for an extended period of time, ensuring continuity in the government’s efforts to combat the disease. The position was discontinued in 1957, as there were only seven people who had experienced leprosy remaining in Norway. At that time, Melsom concluded that he was no longer needed.

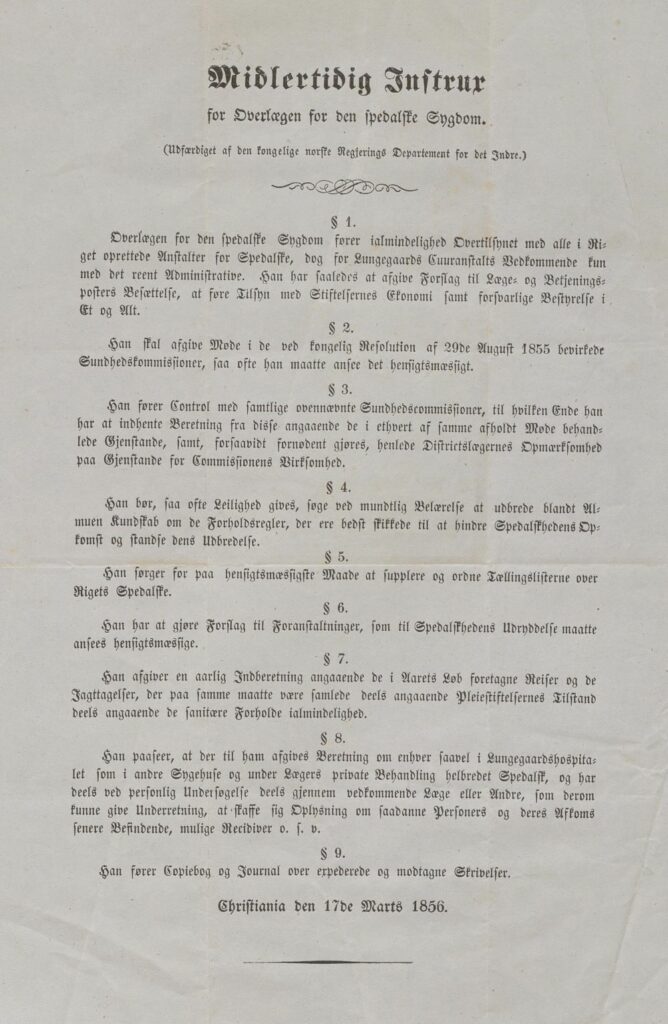

The Chief Medical Officer’s duties

One of the Chief Medical Officer’s primary duties was to participate in the management of the state care institutions. The physicians at the hospitals Reitgjerdet in Trondheim, Reknes in Molde and Pleiestiftelsen in Bergen were directly under the chief medical officer’s authority, while Danielssen at Lungegård Hospital had a more independent position. Another one of the chief medical officer’s duties was to disseminate knowledge about the disease to the public to help prevent its spread.

Ove Guldberg initiated the national counts that are now known as the National Leprosy Registry of Norway. These lists were intended to provide a better overview of the spread of the disease, to help find its cause, and to assess the effectiveness of any measures introduced. The most important duty of the medical officers was to monitor the national counts. Their duty was to assist and monitor the district medical officers, and from 1857, to do the same for the health commissions that were established in all districts where leprosy was present. Together, they were to ensure the registration and monitoring of everyone with leprosy across local communities.

It was a time-consuming task to collect reliable information about every single person diagnosed with the disease. People could easily slip through the net and not be reported, and for those that were registered, doubts could be raised about whether or not their diagnosis was correct. The medical officers spent a great deal of time sending out directives, reminders about registration procedures and deadlines, as well as assessing applications for admission. They also travelled around the districts to assist district medical officers with diagnoses, especially in cases of doubt.

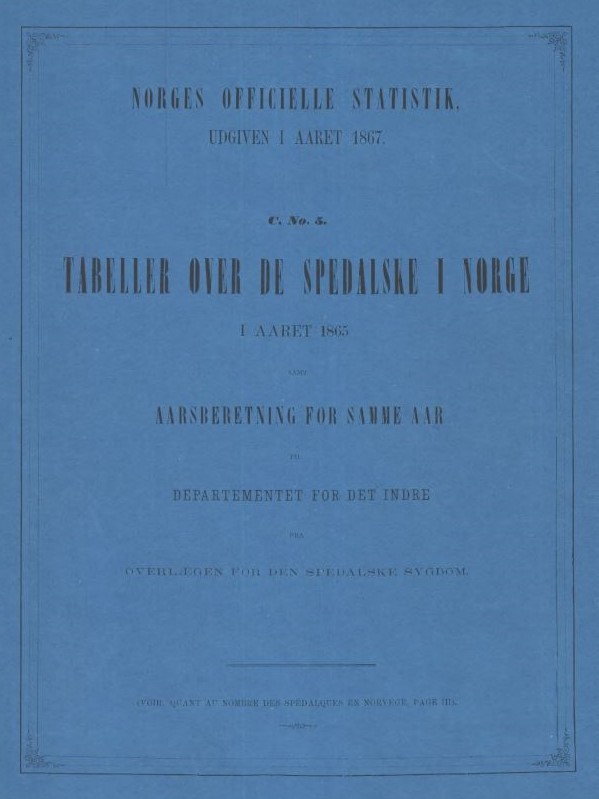

In addition, all the national counts had to be arranged and supplemented, and records and reports had to be produced. From 1860, the chief medical officer was responsible for publishing annual reports, including extensive statistical material. ‘Tables of People Diagnosed with Leprosy in Norway’ was initially published annually but from 1881, it was published every five years.

The Regional State Archives of Bergen.

‘Tables of People Diagnosed with Leprosy in Norway’ , 1865.