Contact with the outside world, home visits and escapes

As a general rule, those who were admitted to Pleiestiftelsen were to stay within the hospital grounds, but even during the first few years, a small number of residents are said to have been allowed to leave the hospital for parts of the day, and that they then often carried out small errands in the city. Other contact with the outside world included regular visits ‘from acquaintances and relatives from their native districts’.

Head Physician Løberg states that a few of the residents were allowed to make a short journey home in the summer to visit their family, although this was normally limited to four weeks or less. He was in doubt as to whether he should continue to grant permission for these home visits, which he believed often caused various ‘irregularities’, but he feared the consequences of denying everyone permission to visit home. He describes the huge extent to which some residents missed home, and that he was afraid that their ‘homesickness’ – especially longing for their children – may become so strong that some might lose their minds.

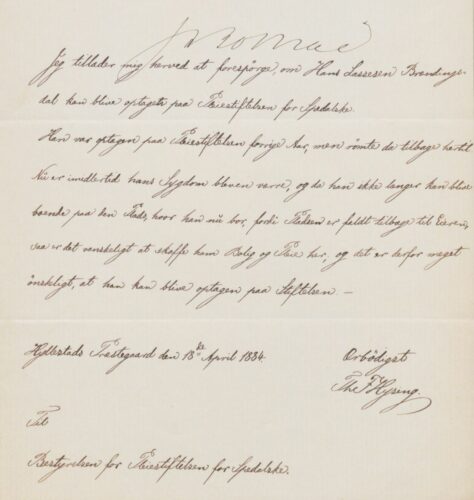

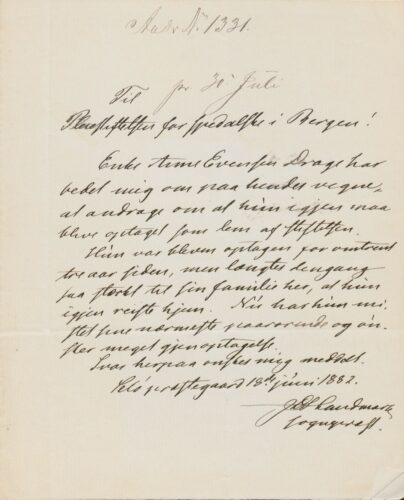

Løberg found that most people who were allowed home returned to the hospital, and that some of those who were not allowed to go home escaped. A number of escapes were noted in the first decades. The escapes were sometimes explained by patients being obstinate and unable to abide by the order and way of life at the hospital. At other times, escapes were put down to homesickness. Some of those who escaped, or who were allowed to travel but did not return, asked to be admitted to the hospital again after spending a short or long period at home.

Eventually, those in charge realised that it might discourage people from applying if those admitted were never allowed to return home. In 1872, one of the district medical offers in Western Norway wrote that reluctance to be admitted to the Pleiestiftelsen increased year by year, and that the reason for this was that those who were admitted were not allowed to make short visits home, not ‘even to see loved ones on their deathbeds.’

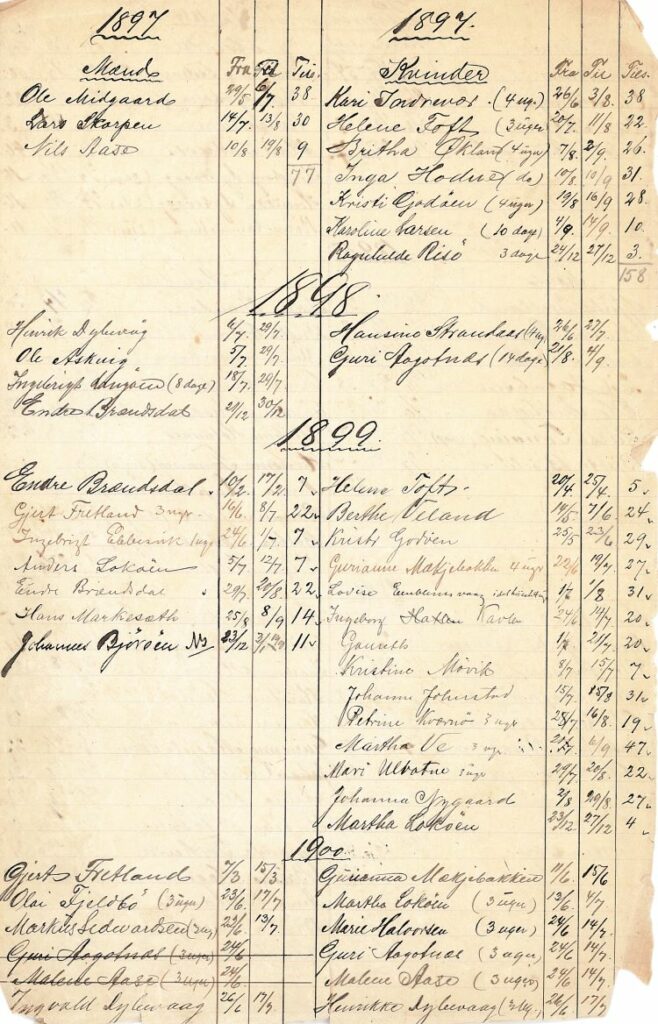

At the end of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th century, trips home in the summer were quite generous. In 1889 and 1890, 35 people were granted home leave, totalling 1,363 days. Between 1911 and 1915, 51 people visited home, totalling 1,043 days.

The Regional State Archives of Bergen.

The Regional State Archives of Bergen.

The Regional State Archives of Bergen.