Description of St. Jørgen’s Hospital and Church

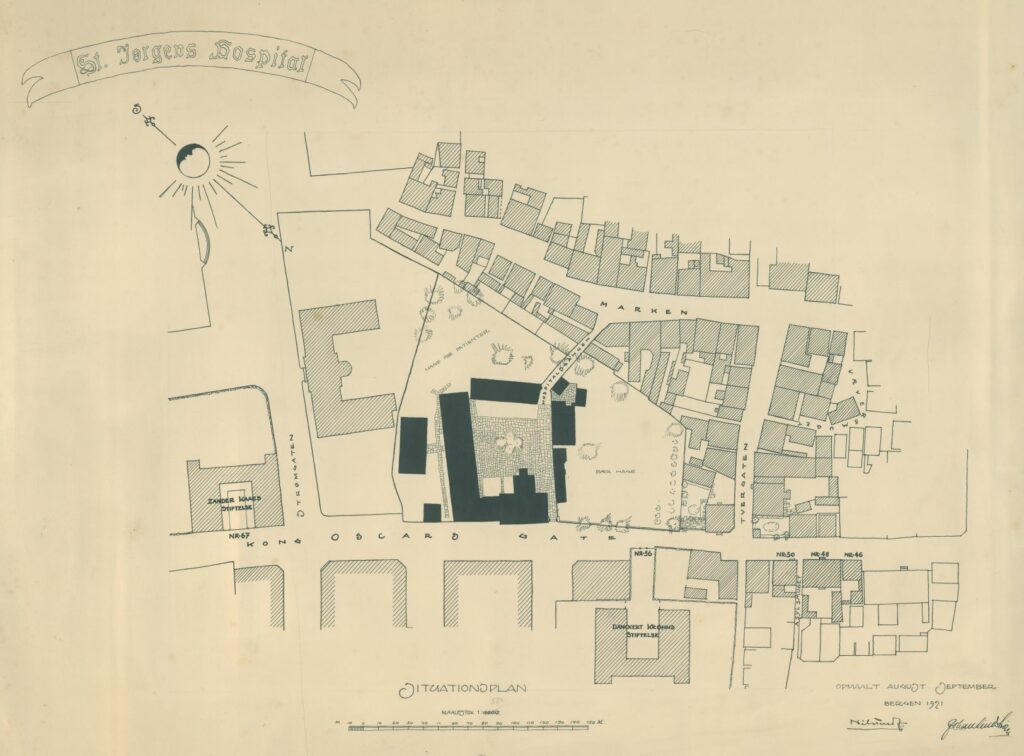

Idyllic – like a monastery made of wood, the hospital St. Jørgen’s is situated in the heart of Bergen.

The tranquil equilibrium and amiability that characterises the buildings are in stark contrast to the newer buildings around it that, especially in Kong Oskarsgate, have wreaked havoc with the urban landscape and the tradition of good, healthy architecture.

The church and the hospital must have been in harmony with the earlier wooden buildings, of which only Sander Kaaes Foundation and Dankert Krohn’s Foundation have survived, in addition to some more or less neglected town houses.

The present church is from 1702, when it was rebuilt after the fire that ravaged most of Bergen at that time. It is constructed using approximately six-inch timber planks with exterior uprights and plain cladding. The roof structure is ordinary. A rafter roof with collar beams and purlins. The steeple rests on four coarse wooden supports rising from the ground. From older descriptions, it is noted that the steeple spires previously had a copper roof, it now has slate, and is probably not its original shape. The other roofs are covered with black, curved pantiles.

The structure of all the buildings is roughly the same as in the church.

The interior has undergone major and minor changes, such as the demolition of the side gallery in the nave. This went from the present gallery to the corner of the transept and nave wall, and the steps were where the stove now stands. In connection with this gallery, a gallery once spanned the entire transept, of which only a remnant now remains.

The organ gallery installed in the 80–90s is new and unsightly.

Two chimneys have been built in the nave – one on each side of the choir, with their monstrous stoves. These are now, however, of less importance, as electric heating has since been installed in the church.

The choir entrance had a door with long turned balusters, and similar balusters in the side openings.

The most recent change is the over-painting of the nave and choir, with the rococo colours being replaced with the vapid shades of brown and yellow fashionable in the 80s.

The walls and probably the ceiling were originally pale yellow-white, the pews white with a blue handrail. The pulpit and altarpiece were kept in white and gold with blue-marbled panels.

By simple means, especially by returning the interior to its original colours, the benefit to the church will be so significantly that restoration is unquestionably worthwhile.

From the sacristy of the church, one enters the main building’s main ward, which has a total of 40 bedchambers on both sides, half of which are located along a circular gallery, with stairs leading up from the ward.

The ward is somewhat changed. It once had two large free-standing fireplaces where the present chimneys now stand. Furthermore, it had a beamed ceiling. The doors were yellow-brown, reddish-brown panels with black mouldings and the walls were whitewashed.

At the lower end of the ward, one enters a paved hallway with stairs leading up to the first floor. At one time, the hallway and the kitchen behind it were one room. The kitchen has a flagstone floor. In the middle of the floor is a free-standing double fireplace. Along the walls are a number of cupboards for patients.

This kitchen is connected to the small ward’s kitchen, from where stairs lead up to the first floor. From the kitchen, one enters the small ward, which has 16 bedchambers, half of which are located along the gallery with stairs that leads up from the kitchen.

The small ward was originally intended only for healthy people from the countryside, who bought a place for life. The main ward, on the other hand, was only for the sick. On the first floor above both kitchens are rooms for the servants.

The building was constructed in 1754, while the main building behind is said to be about 30 years older. It comprises a hallway, a kitchen and two rooms on both sides of each floor. The building is now rented to the homeless, and as a result, its interior has been extensively altered. Its appearance is of less interest.

In addition to the large main building, around a paved courtyard – with old lilac trees in the middle – there is the superintendent’s residence and an outbuilding.

The superintendent’s residence or sexton’s residence, as it has been in its time, was built in 1776 on the old plot of the sexton’s residence.

The layout is largely unchanged. The building’s windows with mouldings facing the courtyard have been removed and replaced with the ordinary: popular Swiss-style frames, which, in no small way, spoil the simple form of this small building. The superintendent’s residence includes to the southwest an enclosed courtyard with a woodshed, washroom, WC, etc.

Flush with the superintendent’s residence, there are several storehouses, which tie the complex together with a simple, beautiful gateway towards Kong Oskarsgate. Directly across the courtyard on the other side is a similar gateway, which leads into Marken.

In the outhouse, there was once a cowshed with a hayloft above it. The building is now used to store firewood and as a work shed.

The complex is surrounded by two old gardens – the large orchard behind the superintendent’s residence and the south-facing garden for patients behind the cowshed.

Bergen, September 1921.

Nils Tvedt Johan Lindstrøm