Early curative attempts – quicksilver and charlatans

As early as the 18th century, the city physician Jacob Woldenberg (1649–1735) conducted research aimed at finding remedies that could cure leprosy. He was granted permission to conduct experiments on five selected patients from St. Jørgen’s Hospital in 1711, after setting up a ‘hospital room’ connected to his private residence. Those sent there were put on a ‘peculiar diet’, and after 6–8 weeks, four of them were declared healthy and sent home. The fifth patient died during treatment. However, the four patients that had been deemed cured soon became ill again, allegedly because they neglected to follow the diet and use the medicine they had been prescribed. Two of them died before they could reach the hospital, while the two others were readmitted.

The next city physician that attempted curative trials was Johan Andreas Wilhelm Büchner (1730–1815), in the early 1760s. The catalyst for these trials was reportedly a retired officer and avid reader of medical literature who told of a successful mercury treatment of ‘those afflicted by venereal disease’. Büchner was sceptical, but nonetheless undertook to trial the same treatment on leprosy patients. Four or five patients were transferred from St. Jørgen’s to the newly established hospital for the poor on Engen, where the treatment would take place. When the treatment showed no effect after five months, Büchner switched over to the cure he believed would work, bathing and a change of diet. After another five months, three of the patients were deemed cured, while one died during treatment. The cured patients were sent home but returned after new outbreaks of the disease 3-4 years later. Despite this setback, Büchner was still convinced it was possible to cure the disease in its early stages with a varied diet and a sensible lifestyle.

Christian Wisbech (1801–1869) apparently tried to treat leprosy for years but concluded after countless experiments at ‘Det Civile Sygehus’ Hospital starting in 1826 that the disease was incurable. Despite the fact that some patients displayed few symptoms and appeared cured, the disease often returned in an even more severe form at a later point. When other physicians in the 1830s and 40s advocated for more hospitals, Wisbech believed that establishing more care institutions, particularly treatment facilities, would be a waste of time.

Others also tried to cure the sick. In the first half of the 19th century, there were several instances of people without any medical training trying to cure people with leprosy. Perhaps some of the residents at St. Jørgen’s had more faith in these charlatansthan in the physicians.

One of the more famous of these charlatans in Bergen is Madame Pytter. In the newspaper Bergens Adresse- Contoirs Efterretninger, Lucie Pytter of Sandviken stated in 1804 that leprosy could be cured. At her request, she was allowed to treat two women from St. Jørgen’s Hospital at her home in Sandviken for a few weeks. The details of the treatment are unknown, but both women returned to the hospital with no signs of improvement and died the following year.

In the 1840s, there was another famous woman in Christiania called Mother Sæther. She had gained a reputation for being able to cure the disease. Several patients at St. Jørgen’s expressed a desire to visit her. A couple of patients reportedly travelled to see her in 1847 on the initiative of the hospital’s superintendent, but the treatment yielded no results.

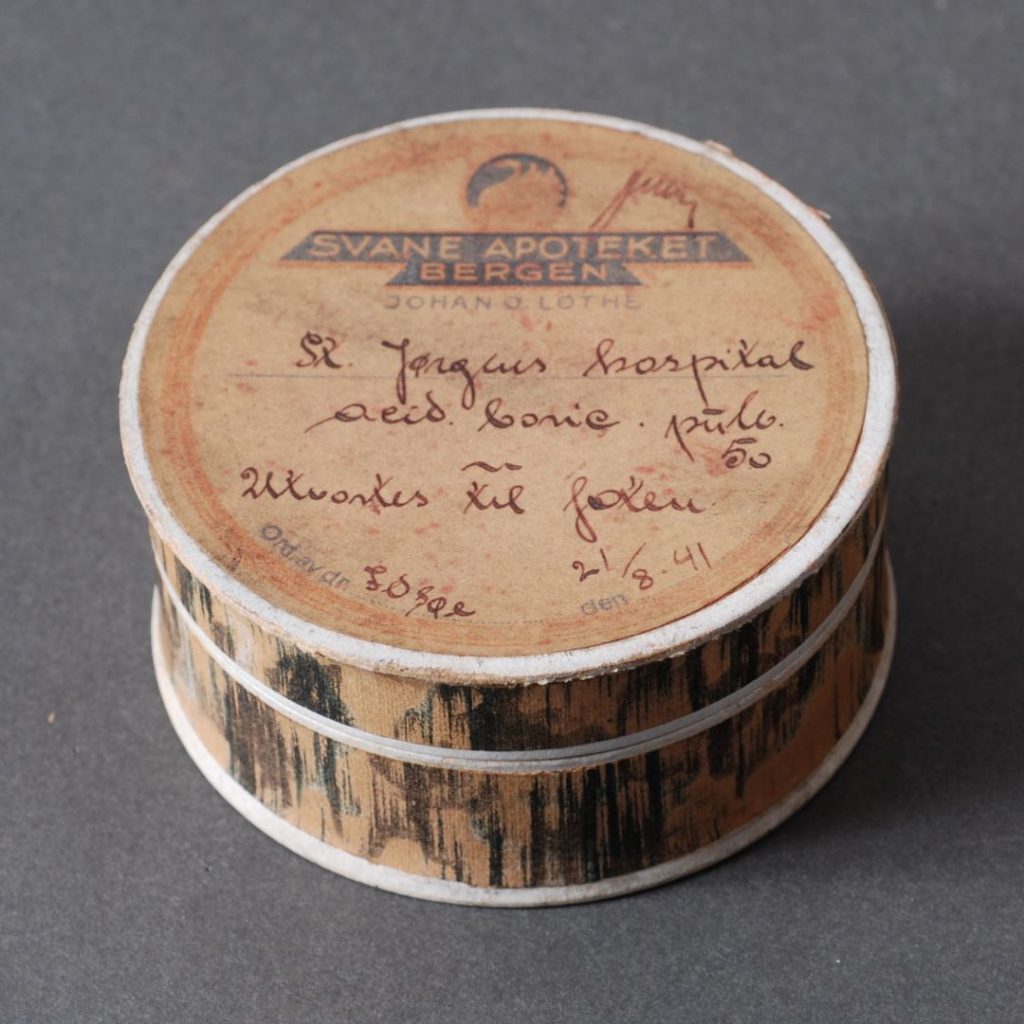

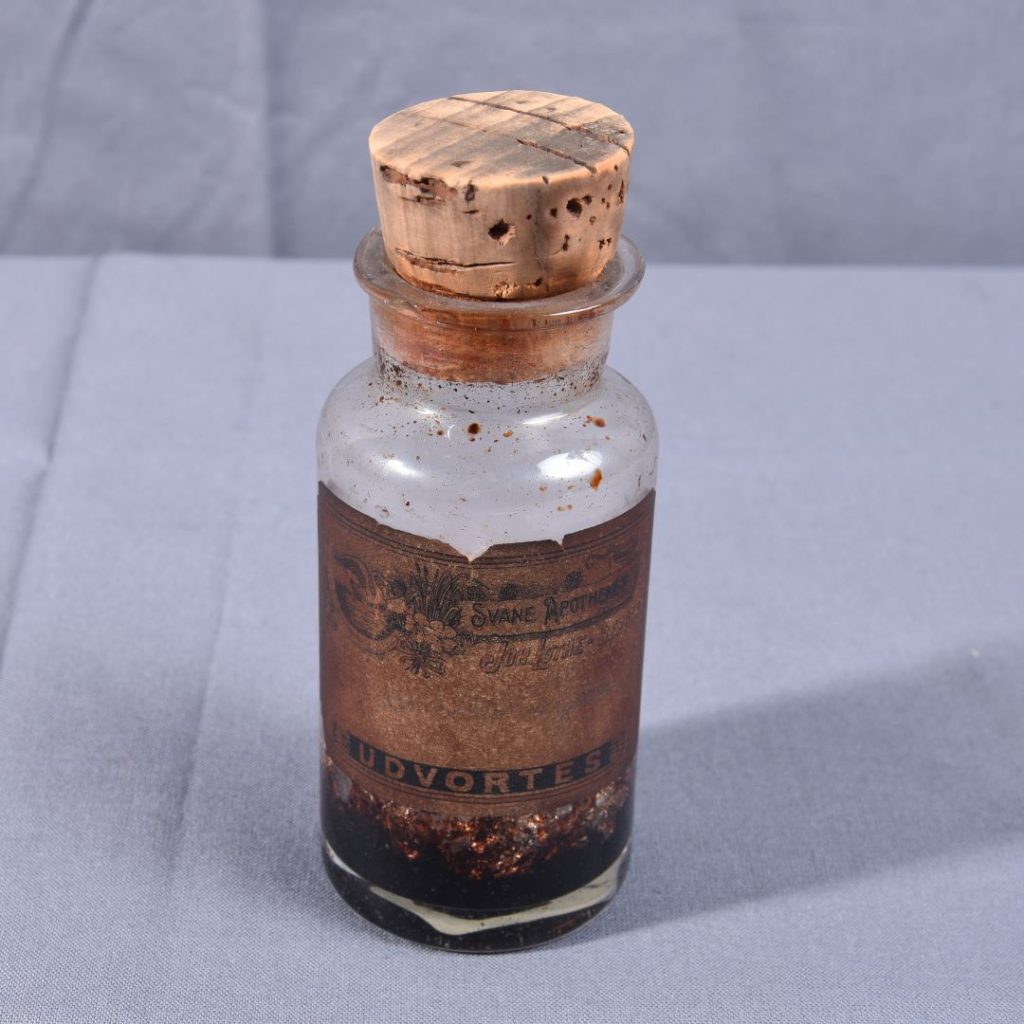

Various remedies from Svane apothecary that were used at St. Jørgen’s Hospital.

Photo: Bergen City Museum.