Work-filled days at Pleiestiftelsen

As at many other institutions, the hospital ensured that residents worked according to their ability and strength. Everyone was obliged to carry out the work they were instructed to do, after their ‘state of health’ was assessed. For a long time, the fixed working hours were from 9am to 12pm and from 3pm to 6pm, and no one could leave their assigned work without notice. Work was considered beneficial for several reasons, including that it helped maintain peace and order. The work also generated income, mostly for the hospital, but often a little for those carrying out the work too.

Work activities also stopped the days feeling too long and helped give residents a sense of purpose and satisfaction. The annual reports mention several times the residents showing ‘much joy and zeal’ at work, and that many of those unable to work because of ‘low physical strength’ missed doing the work. During certain periods, those working were allowed to keep part of the income, and men often bought tobacco.

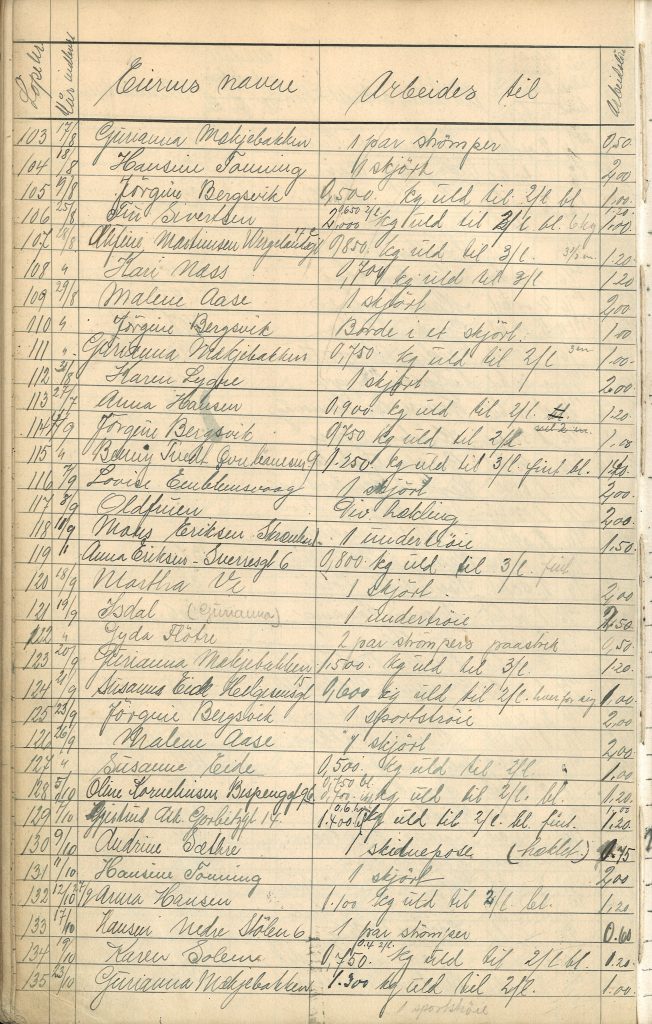

The work partly consisted of making and repairing clothes, shoes, furniture, and other items needed in the hospital, and partly of working for people in the city. The superintendent accepted work from people in the city and ensured the work was carried out for a fee. This work diminished after Armauer Hansen argued that leprosy was infectious. It was considered easiest to keep the women busy with knitting and sewing, everything from towels and handkerchiefs to blouses and children’s clothing. The men’s work mainly consisted of making fishing nets and trawl nets, shoemaking, carpentry and gardening. The annual reports and work records show that a lot was done. In 1863, the men made, among other things, cupboards for the school classroom, 40 bookshelves, 12 garden benches and 67 coffins.

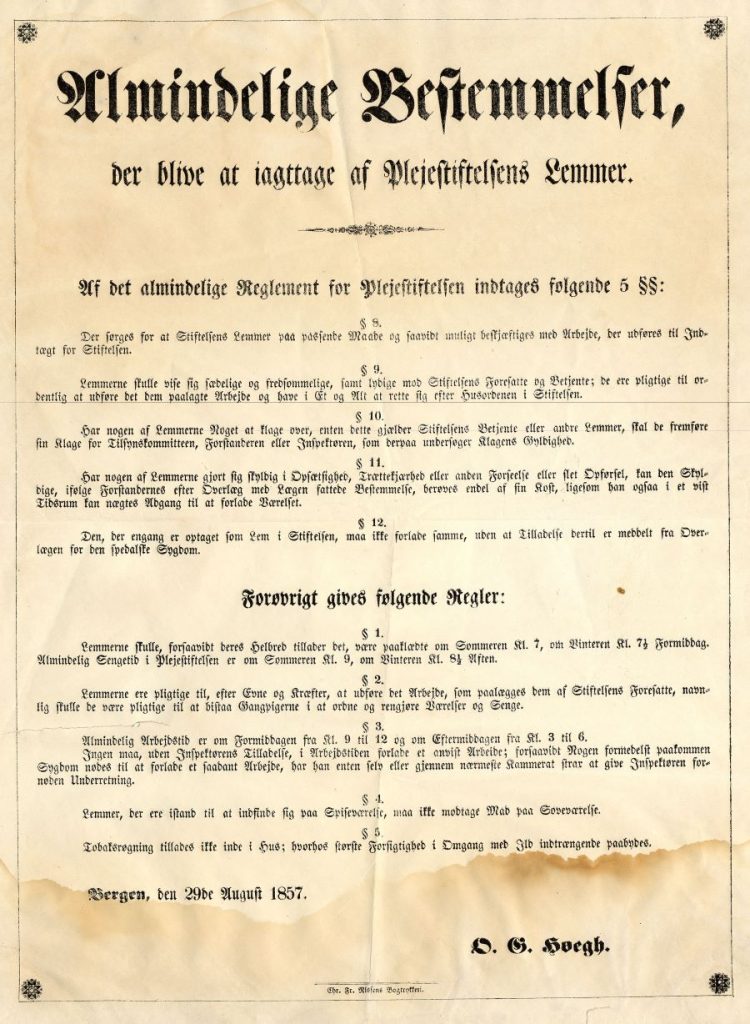

§8: It is ensured that the hospital’s residents are appropriately engaged as far as possible in work that generates income for the hospital.

§2: It is mandatory for residents, according to ability and strength, to carry out work assigned to them by the hospital’s staff, in particular they are obliged to assist the servant girls with tidying up and cleaning the rooms and beds.

§3: Regular working hours are in the morning from 9am to 12pm, and in the afternoon from 12pm to 6pm. No one may abandon an assigned job during working hours without the Inspector’s permission; If someone is forced to abandon such work as a result of illness, he must immediately inform the Inspector, either himself or through his closest comrade.

The Regional State Archives of Bergen.

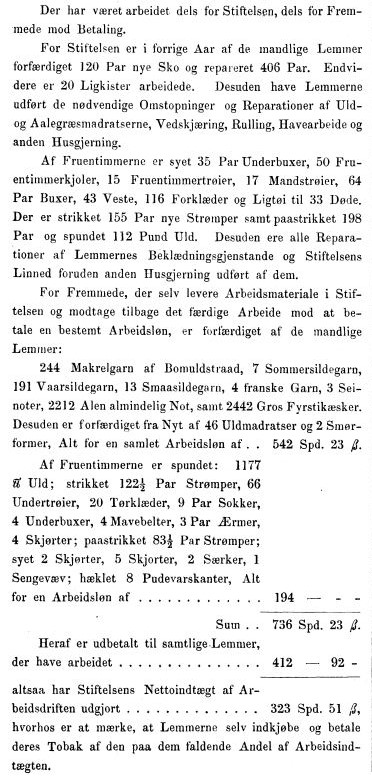

‘Last year, male residents completed for the hospital 120 pairs of new shoes and repaired 406 pairs. In addition, 20 coffins were made. The residents also carried out the necessary stuffing and repairs of the wool and eelgrass mattresses, wood chopping, woodturning, gardening and other work around the hospital.

The women have sewn 35 pairs of underwear, 50 women’s dresses, 15 women’s shirts, 17 men’s shirts, 64 pairs of trousers, 43 vests, 116 aprons, and burial gowns for 33 deceased; 155 pairs of new socks have been knitted, 198 pairs darned, and 112 pounds of wool have been spun. In addition, all repairs of the residents’ garments and the hospital’s linen, as well as other domestic work, have been carried out by them.

For strangers who hand in work material to the hospital and get the finished work back in return for paying a certain wage, male residents have made the following:

244 mackerel nets from cotton thread, 7 summer herring nets, 191 autumn herring nets, 12 small herring nets, 4 French nets, 3 saithe nets, 2,212 ells of regular trawl net, and 2,442 matchboxes. Also, 46 new wool mattresses have been made and 2 butter moulds.

The women have spun: 1,177 pounds of wool, knitted 122 ½ pairs of stockings, 66 undershirts, 20 scarves, 9 pairs of socks, 4 pairs of underwear, 4 abdominal belts, 3 pairs of sleeves, 4 skirts; darned 83 ½ pairs of tights; sewn 2 Skirts, 5 Shirts, 2 sarks, 1 bedspread, crocheted 8 pillowcases.

Of this, a total of 412 Spd 92 Sk has been paid out to all residents who have worked, so that the hospital’s net income from labour amounted to 322 Spd 51 Sk, where it should be noted that the residents themselves purchase and pay for their tobacco from the share of their income derived from their labour.’

From ‘Tables of People Diagnosed with Leprosy in Norway’ 1864, www.ssb.no.